We are a mother and daughter team and have written this cookbook exploring German-Jewish Cuisine as it existed in Germany prior to World War II and as refugees later adapted it in the United States and elsewhere. It is a surprise to many people in the U.S, and perhaps in Germany as well, that these dishes differ from more familiar Jewish food, which comes either from eastern Europe, Israel or Mediterranean countries…

Our project began in 2009, when we began researching the topic, and the book was preceded by a website entitled germanjewishcuisine.com , where we continue to post about the food and culture of German Jews. Food is the most portable expression of a culture, and is a powerful conveyor of historic memory. Therefore, we decided to write this book – in order to document, preserve and share this wonderful cuisine. It still exists in the kitchens of cooks of German-Jewish background, but, until now, was not represented in any contemporary cookbooks (numerous German-Jewish cookbooks were published in Germany between the late 1800s – 1930s). Some of these foods are purely German and since they did not defy kashrut law were also enjoyed by Jewish households, such as the Pflaumenkuchen (Zwetchkenkuchen) that is a favorite in late summer. But there are also dishes that were specifically Jewish, such as Grimsele, which is a fried matzo fritter, made during Passover. And on Friday nights and other holidays, every family would have a Berches, the German version of challah, which they could purchase from one of many Jewish bakeries.

Gabriele (Gaby) was born in Bamberg in 1938. Her mother, Erna Rossmer (nee Marx) was born in Munich, as was her mother’s mother, Emma (nee Westheimer). Gaby’s grandfather, Sigmund Marx, was born into a large family that lived in Noerdlingen until they moved to Munich around 1900. He and two siblings co-owned a lithography factory in Munich named Beger und Roeckel, with a division named Grafia. They made greeting cards and paper wrappers for chocolate.

Gaby and her parents, Erna and Stephen Rossmer (nee Rossheimer) emigrated to New York in 1939. Sigmund and Emma Marx followed in 1940. They lived together in an apartment in Washington Heights, upper Manhattan, which was home to the largest German speaking Jewish community in the world during and after World War II. It was a community of over 20,000 and living there, the Rossmer-Marx household continued the food traditions of their past. They cooked and ate traditional German-Jewish food, went to a synagogue that was led by Rabbi Leo Baerwald, the former chief Rabbi of the Munich congregation (who had officiated at their wedding in Munich in 1936), and shopped in the butcher shops and bakeries that were owned by their fellow emigres.

Emma was the chief cook in the household. She came to America with two cookbooks. First, the handwritten book from the Muenchner Kochschule, which she had attended as a young woman. Second, she brought “Kochbuch fuer die einfache und feine Juedische Kueche”, by Marie Elsasser, published in 1900. On special occasions, Oma made our favorite dessert, Weincreme, and on children’s birthdays she made her wonderful Igel. Other specialties made by her included Krautsalat, roast goose, meat soup with matzo balls, and vegetables in einbren.

When researching and writing our cookbook, we gathered recipes from a wide variety of sources – some were family recipes we grew up eating, others we got from friends and people we interviewed, yet others we developed from recipes we discovered in these books (and other) historic German cookbooks. In addition to Elsasser, they include books by German Jewish cookbook authors such as Rebekkah Wolf and Henny von Cleef. The recipes needed developing because old recipes typically do not include much of the information equated with modern recipes, such as quantities of ingredients, cooking temperatures or times, and detailed instructions.

Sadly, Gaby’s father, Stephen Rossmer could not save his parents, Hugo and Rosa Rossheimer, from being murdered by the Nazis. They were deported from their Bamberg home in April, 1942 to ‘east of Lublin’. The family never learned any detailed information about their fate. Stephen, an optimistic person who also loved food and the city of his birth, Bamberg, collected recipes from friends and family and started cooking and baking the foods that his mother had once made. From his sister in Israel, he received the recipe for his mother’s favorite Pesach cake, Kaisertorte, made with a layer of apples between two layers of nut-filled dough.

Our book combines the recipes with stories, history and memoir. Even though it is a book about Jews all over Germany, the background is very much rooted in Bavaria, since that is our familial homeland.

We have been travelling across the U.S. – and now Germany – giving book talks and cooking demonstrations. We have found a large amount of interest from people who have German-Jewish background, but also from Germans and from Americans, both Jewish and non-Jewish. During this visit to Germany we will be giving a talk at the Municipal Museum of Bamberg, and presenting numerous food events in Berlin. On a previous trip to Berlin, we encountered tremendous enthusiasm for our subject while teaching a cooking class and hosting a pop-up Pesach meal. We have seen that Germans are yearning to know more about the real lives of Jews.

If anyone wants to talk some more about the book, or about this food tradition, please contact us at german.jewish.cuisine@gmail.com.

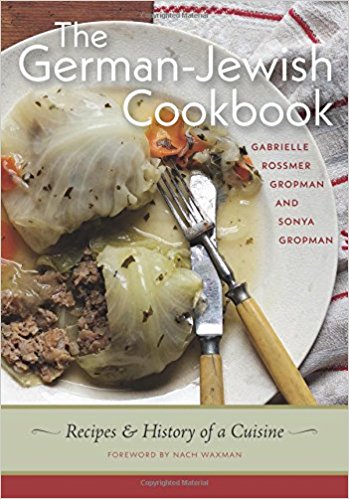

“The German Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine” by Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman, published by Brandeis University Press, September, 2017