A Dialogue with Rudolf Ekstein…

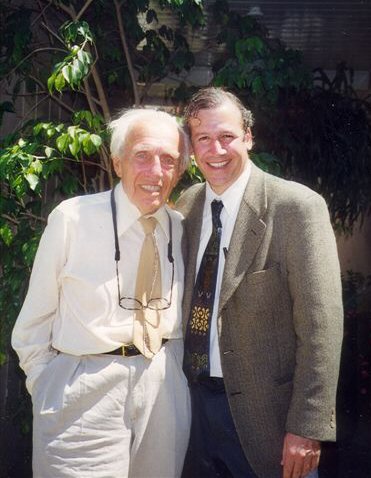

Daniel Benveniste (Bellevue, Washington) (1998)

“I was between 22 and 23 years of age but in 1935 there was already a fascist government. As a socialist, who was Jewish as well, it would be impossible to ever to get a professorship at one of the high schools but I resolved to do anything and I passed all the examinations. I went to the University for philosophy, went to Bergasse for psychoanalysis, and a few blocks away I went to where socialist students had their headquarters. And between these three points was the life of this young man.”

Rudolf Ekstein (1998)

Rudolf Ekstein, Ph.D. is an internationally known psychoanalyst who has written numerous publications on psychoanalytic topics such as psychoanalytic supervision, child therapy, psychoanalytic pedagogy and a variety of clinical and historical topics. He received his psychoanalytic training in Vienna from 1935-38 under Willi Hoffer, August Aichhorn, Anna Freud and others. His emigration in 1938 took him from Vienna to England to Boston to New York to Topeka and on to Los Angeles. The edited dialogue before you is about his training and emigration and the people he met along the way. As an edited dialogue, it is a condensation and displacement of two personal interviews conducted at his home in Los Angeles and one public lecture. The lecture, entitled The Emigration of Psychoanalysis from Vienna to Los Angeles, was presented in a symposium sponsored by The Friends of the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute on September 23, 1995. The symposium, The Emigration of Psychoanalysis from Vienna to California included additional presentations by Hildegard Berliner, M.S., Haskell Norman, M.D., Beulah Parker, M.D., and Daniel Benveniste, Ph.D.. Dr. Ekstein’s slide and lecture presentation reproduced for the audience a similar experience to my interviews with him at his home in Los Angeles, which is a veritable museum of psychoanalytic memorabilia including photographs, old books, and other psychoanalytic artifacts. His lecture was illustrated with slides of Viennese psychoanalytic luminaries, many of whom he knew personally. The photos were drawn from books on psychoanalytic history and from Dr. Ekstein’s personal collection. Thus, you will find the following edited dialogue partially organized around some of these photographs. So if you will, I’d like you to imagine this dialogue, taking place, as much of it did, while the two of us are sitting on a couch together in a room filled with old psychoanalytic texts, antiquities, and old photographs.

DANIEL BENVENISTE: Dr. Ekstein, as a psychologist, I am not only interested in the stories of how my patients got to be the way they are but also how psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy got to be the way it is. Your career has spanned an extraordinary piece of psychoanalytic history and so I am interested to hear your story.

RUDOLF EKSTEIN: One sometimes wonders, when one thinks about the past, „How did I become what I am? From where do I come? and Where am I going?“ When one is my age, the question of „Where am I going?“ is less interesting. So I ask myself, „From where do I come?“ and so I’d like to tell you how a young man comes to psychoanalysis.

Originally what I wanted to do was to study psychology at the University of Vienna. I wanted to be a psychologist and a philosopher. But it was not very easy because the psychology that was taught at the University was not really what I wanted because I knew there were streets right next to the University where a completely different psychology was taught. I don’t know if you know Vienna but I will describe it.

It was a long, long time ago. There was a district in Vienna, the 9th district, where I grew up. Its a strange district. The people that live there in one part are lower middle class, in another part, workers – certainly not rich people – but this district had a special meaning for me. Because when you walked in this district you came upon points of culture. From my house it took me two minutes to go to the birthplace of Franz Schubert, seven minutes to go where Beethoven lived, eight minutes to where Freud was, and nine minutes to the University. If I went into one street, there was Alfred Adler, on another street there was Freud or I could go to the University where there was Schlick and Reininger and Waissman and Gomperz and Kahler and Max Adler and Charlotte Bühler and Karl Bühler and it was in this small unbelievable world that I grew up. You were surrounded with an intellectual environment that was hard to believe.

There’s a Catholic church there with a monument to Schubert who played there and created his music there. If I walk a little farther, I would come to a building where Tandler began He was a famous professor of anatomy who later had, like all of us, to escape. He escaped to China. But if I went two minutes in another direction from my house there was a place, Kinderübernahmestelle, for children where they would be taken care of when they were in trouble. It was created by Charlotte Bühler, of the University together with Julius Tandler and other assistants.

When I walked from my home to the University, along Wühringerstrasse, I came to a crossing. If I would go to the right it would be Schwarzpanierstrasse and if I would go to the left it would be Bergasse. And the question, now, was „Should I turn to the left or should I turn to the right?“ If I would turn to the right there was the home of Alfred Adler. If I would turn to the left there was Sigmund Freud. But I did neither want to turn to the left nor to the right because I wanted to get to the University. And I would go to the University and there were my teachers Karl and Charlotte Bühler and above all Moritz Schlick.

DB: Yes, I saw the picture of Moritz Schlick in your study. He has a very kind expression on his face.

RE: Schlick was a great and interesting person. I had to go through all the other philosophers, the history of philosophy, the Kantian point of view or whatever point of view this or that professor was. But Schlick was not this way. He did not really invent a new philosophy but rather he had a philosophy in which he asked what is really meant by this or that? what did the philosophers really mean? You don’t have to be a follower of Kant or Schopenhauer or Hegel or Marx, or, whatever it was. The question is can you understand what they meant? and can you slowly try to find a language by means of which you could communicate? And that is very similar to psychoanalysis, because when we want to understand someone who conveys something to us even if it is in a language we carry, we have to learn a new language. We have to learn the language of the unconscious. We have to learn the language of the preconscious. We have to learn the language of the waking spirit, of the dreaming person, of someone who is not quite awake and is half in a dream. And so having a philosopher who said, instead of insisting on one kind of philosophy, „You have to understand the philosopher but you don’t have to, as it were, carry it with you.“ So I slowly developed a bridge from Schlick the philosopher to Freud the psychoanalyst.

When I wrote a term paper for Schlick, he gave me the term paper back and he said to me, „You gave an excellent account of my thoughts but if you want to be a doctor of philosophy you must have thoughts of your own. Unaccepted!“ At first there was anger that he didn’t accept it. Then I got depressed. „I will never amount to anything. I must hurry to get the doctor degree. I will never get it.“ And suddenly the thought comes to my mind, „I can have thoughts of my own?“ And I wondered, „Can you write a dissertation that has thoughts of your own?“ I had learned before „You’re not here to have thoughts of your own. You’re here to repeat the thoughts of your teacher and prove to him that you learned what he’s teaching.“ But Schlick was a philosopher of a completely different sort. He said „You must have thoughts of your own.“

I had to rewrite the thesis and then something very terrible happened. He accepted the thesis but before my oral examination he was killed on the steps of the University. He walked up the stairs of the University, a man came, saw him, and shot him dead. It was a story about a love affair, of which we’ll never know how much was true or not. It may be that it was this way – that he had a love affair with a younger woman and the betrayed man shot him dead. That was already the beginning of Nazi time and when the Nazi’s came to power, they let the man out of jail. This was the way life was at that time. So Schlick, for us, was a memory. He had just accepted my dissertation but I could not have the oral examination with him so I met with another professor, who was friendly with Schlick, Reininger and the others. And there was always the fear of „What must I say to pass? What if someone examines me and he has a different philosophical belief than Schlick? But it went fine, and no sooner did I have the doctoral degree that I knew the time had come to escape or go to prison. Freud escaped. He went to London and my escape also began in London. Freud was still alive – no more Schlick – and a little while later, in 1939, we lost Freud too. It was now a life where one’s intellectual fathers belonged to the past. Fascism came and I had to gather together all that I had and to see what I could do in another country and to have thoughts of my own.

So I escaped as a philosopher and a psychologist – the Bühler school of psychology and the philosophy of Schlick and Reininger and Gomperz. I was absolutely unknown. When I got to England the only bridge that I had was another person who escaped – Anna Freud. So I could continue with the analytical work and the training I had started.

DB: Well what about your analytic training in Vienna? How did you make your way from the University to the analytic community?

RE: Before I went to the analysts, I went to Alfred Adler’s lectures. So for a while I was in danger to become an Adlerian! Adler was a Socialist or Social Democrat so that’s where I had to go. And I learned from his lectures, long before the Freudians. I studied with him for one or two years, and all of that only five minutes from the headquarters of the Socialist students and five minutes from Freud and five minutes from the University. One always had the feeling, when one sees Adler, that this is an angry man. And I wonder sometimes why he developed the concept of the inferiority complex and if maybe he didn’t think he was inferior to the one on the other side of the street. But those are speculations. So when I began, it was with Adler. I was in seminars with Adler for about a year or two. But then I did something strange. I crossed the street and went to another lecture.

DB: Before getting to that other lecture across the street I am curious to know, were you attracted to Adler because of his Socialist activity?

RE: Yah, I would say that the beginnings of my work came out of a social desire to help – to make a better world. I felt there should not be the world of the post-war (World War I) Vienna, where we all went hungry, where there was unemployment, and where there slowly came fascism. So my interest was, in part, to help people, and, in part, to change the whole world. I became political and as I became political, I understood we can only change the world if the people who are supposed to help you change the world are willing to change the world. What kind of people are willing to change the world?

People who understand themselves, who have ambitions, and will not be the victims of movements such as drive by shootings here in America or of drugs or of alcohol – and there were plenty of these kinds of problems in Vienna. Its true in every big city.

And then I was once at a summer home and some people had an interesting book that they wanted me to read. They knew I wanted to be an educator. The book was „Sisyphos or the Boundaries of Education“ by Siegfried Bernfeld. He was a man who ended, as you know, in San Francisco. I read the book and I realized it was so much up my alley because it had a combination of psychological thinking and sociological thinking and I asked my friends at that home, which was outside of Vienna somewhere in the mountains, „Where can you learn these things?“ And they said „Don’t you know, in Vienna there is a movement under the leadership of Anna Freud, of August Aichorn which trains psychoanalytically oriented pedagogues. Some high school teachers go there and elementary school teachers go there. Kindergarten teachers go there.“ And in 1935 I went there. I was accepted by Willi Hoffer. I went there and the road changed. I was between 22 and 23 years of age but in 1935 there was already a fascist government. As a socialist, who was Jewish as well, it would be impossible to ever to get a professorship at one of the high schools but I resolved to do anything and I passed all the examinations. I went to the University for philosophy, went to Bergasse for psychoanalysis, and a few blocks away I went to where socialist students had their headquarters. And between these three points was the life of this young man.

DB: Did you ever find these different world-views in conflict?

RE: Yah, at that Schlick seminar I had a very interesting and strange encounter – namely Siegfried Bernfeld came to Schlick’s seminar and he had a very difficult time

with Schlick. He had a very difficult time because he thought, at that time, that one could measure libido Bernfeld would say that psychoanalysis will never be a science unless it is quantifiable which, of course, is one of the main objections to psychoanalysis to this very day. To make it acceptable to the rest of the psychological world, one must measure it.

Whenever I think of that issue with him I think of the famous words of the philosopher who says „Where counting starts understanding stops.“ And I added to that, as would Bernfeld, „Where there is understanding, counting should follow.“ In other words, we owe it to the world. We need scientific investigation. Even though some of the cientific activities, to us analysts, who are in practice, seem naive, we need them. When you take someone’s temperature and you measure it, you can ask, „What is between 38 and 39 Celsius? What does it mean? When does it become dangerous? Can one then read into it what is the real illness.?“ The illness is not just temperature. Temperature is just one of the symptoms. So from the wish to become scientific which you hear from all the Universities comes the new thought „I must measure. I must measure. What should I measure?“ So for me it was one of those unbelievable experiences I can still see him in the Viennese seminar. I know exactly in which street it took place Liebiggasse where one was sitting and where the other was sitting.

Bernfeld tried to discuss the notion that he and Feitelberg had developed, the notion that one can measure libido. They had developed a whole scheme for measuring libido. And I remember Bernfeld didn’t have a good time of it with Schlick, because Schlick could show him that the concept of libido can, at best, only be conceptualized in terms of more or less and that we have no way to measure it. But for Bernfeld it was very important to measure. He felt that every science must be able to measure. I don’t know if Freud ever thought one could measure libido. I thought when he spoke about psychic energy he didn’t go farther than speaking about more or less libido. The concept of measuring libido is not quite applicable. I remember Bernfeld sitting in the seminar of Weissman and Schlick and for me at that time it was a very difficult situation because I went two ways. I remember the inner struggle. Am I to believe in him to whom analysis is important along with Marxism and socialist thinking or am I to believe in him who says „I will teach you how to have thoughts of your own and how to think.“

So as you see I had, in Vienna, an unbelievable time. But none of these teachers permitted me to say „I will be just the follower of one and not the follower of another.“

So I had not to follow Adler or Freud or Anna Freud. I had to learn how to think. Even if I am a direct descendant of Sigmund Freud, I can have thoughts of my own. Freud did not expect that people should be imitators of Freud. In that sense there are no Freudians.

For Freud, people are Freudians when they have studied with him and developed psychoanalytic thinking and contributed something. Freud did not want to have people who just adored him but who have learned to think analytically and developed their own language, their own concepts. In Schlick and in Anna Freud I had people who allowed me to go my own way. Now on my way to psychoanalysis I had at first a rough time because I thought in order to be happier, in order to have a good life you must change the world – or, if you like, you must be a Marxist. And then I discovered Sisyphos and saw that in Bernfeld, there was a bridge between Marxism and psychoanalysis. Read that book again. It’s a marvelous book. Its a book where he tried to unite, in his mind, two ways of being and Bernfeld at that time became for me a saint because he represented to me a bridge between two ways of thinking.

It was a world where I slowly tried, as a young man, to unite the worlds of Marxism, psychoanalysis, Individual Psychology and logical thinking and Siegfried Bernfeld was one of these people who made it possible for me. A good friend of mine in Los Angeles is his daughter, Ruth Goldberg. She is married to Al Goldberg whom I know because he was one of the people who had his analytic training with me.

DB: It sounds like it was an intellectually rich environment but a real challenge to know which way to go.

RE: Yah, it was. I came to psychoanalytic training with this mixture of socialist ideas and ideas about the soul of the person and I discovered that I wanted to be a teacher but a teacher who understands the psychology of the child, a teacher who can think psychoanalytically. And then I met Willi Hoffer, one of the early Freudians. He was my first teacher in psychoanalytic pedagogy. After the first world war, Willi Hoffer and Bernfeld created a new home for children who had lost their parents. Hoffer taught psychoanalytic pedagogy and we all wanted to help in this world and wanted to do it right there. But there were other ways of helping. There was Theodore Herzl, a Jew in Europe who believed there is no way to help in Europe. He said, „You must move to another country. You must go to the promised land. You must change the land. Don’t stay here. Go to the promised land and create for yourself what then will be Israel, the Holy Land.“

There was Viktor Adler, the founder of the Austrian Republic after the world war, after the empire fell apart. He founded the Social Democratic party. He said „We must change the city. You must have a democratic country.“ There was Alfred Adler who would say, „You must change the school system. We must help the children.“ And then there was Freud and he said „You must change your mind and your soul and understand yourself to have a better life.“ I tried all of them and that is why you and I sit here today.

DB: You mentioned Anna Freud being a part of that scene in Vienna. Did you know Anna Freud?

RE: Did I know Anna Freud? When I heard Anna Freud the first time I gave up philosophy and decided I would be an analyst. And I had good professors – famous professors. Come on, come on. Did I know Anna Freud? Here (pointing to a picture of Anna Freud on the wall) you see – Anna Freud in London – in the last years of her life. And when you imagine yourself sitting in front of her, what could you hold back? Just look at that face. „Well?“ she says „Well?“ I was accepted for training back in 1935. Did I know Anna Freud?

When I came to Bergasse 19, although the Institute itself was also at Bergasse but a little nearer to Wühringerstrasse, I had found a place. That was in 1935. I was then a 22 year old boy. In Vienna you could develop an interest in psychoanalysis without already having to have a doctor’s degree. It was expected you would do that anyway but it was possible for lay people to be accepted too. After all Anna Freud was a lay person.

She didn’t have a medical degree. And it took some time for her to finally be accepted in America. If she would have been a refugee and come to America, I don’t believe she would have become a member. She visited us several times. You can see her in this picture that was taken when she was teaching here in Los Angeles.

I wanted to be a psychologist and even though Karl and Charlotte Bühler were highly interesting for me, it was not enough. I did not just want to be a theoretician. I didn’t just want to be a scientist. I wanted to be someone who helps people, who educates people. I wanted first to become a teacher and I found the Adlerians and then the Freudians. I wanted to be a teacher because I felt we could change the world if the young people are different. In the old world it seemed we needed world wars. We, however, are different, I thought. We can have a peaceful and democratic society but democracy begins at home with the parents. I became now a teacher, interested in parents, interested in children, interested in children that could not learn. As a matter of fact, beginning at 14 years of age, I began to tutor children and learned to understand them. I was much nearer to them, in age, than the professors. Just today a had a letter from a man who must be now in his early 70s. He tells me he had just changed his address. I tutored him when he was a little boy. He became an engineer. He had a successful life. The relationship still exists. That is true for many others. That was the beginning.

DB: What was the nature of your psychoanalytic training in Vienna?

RE: I was primarily trained in Vienna in psychoanalytic pedagogy. I had teachers like Willi Hoffer, Anna Freud, August Aichorn, and Helene Deutsch. My field was psychoanalytic pedagogy but I was taught and supervised, by Willi Hoffer, Edith Buxbaum, and August Aichorn, to do analysis. Every good teacher is a little bit of a therapist. I would go into the homes in Vienna and work with children or they would come to my home. I would bring the case to supervision and my supervisors would help me slowly. I would walk around with the boy in the park. That was the therapy or I would crawl around on the floor, under the bed of his parents. One boy said he didn’t want to study and I said, „Okay great! I don’t want to teach you either. Let’s spend the time under the bed.“ Then he says he wants to study so I say „Okay lets go study.“ Then he opens the window and says „I’m going to throw myself out of the window.“ I say „Please, throw yourself out of the window.“ And he says. „You would let me kill myself.“ And I say, „If you think its more important to be killed than to study.“ So then he says, „Okay, lets study.“ He’s a successful old man now in England.

DB: Who is this a picture of?

RE: This is August Aichorn. Now August Aichorn was an unbelievable man. He’s the one who wrote Wayward Youth – Verwahrloste Jugend – an unbelievable book. He brought together, in a home, all these people who were delinquents. He took them out of prisons. They were Verwahrloste, the wayward, and he helped them to become different people and the way he did that was very important for me because, at that time, my ambition was to be a psychoanalytically oriented teacher and maybe a therapist.

He had such a friendly face and his main talent was that he could out-do all these youngsters – he out-delinquented them. He had a way to present himself that they identified with and by identifying with him he helped them to find a way out of waywardness. They identified with him saying „I go with him because he’s a bigger gangster than I am.“ and in this way they became Aichornians! Marvelous! I used to go to the place where he had his children and worked with them and interviewed such children and so I learned to work with delinquent children. I had started to be a high school teacher but in order to make a living I started to teach and to take children as their Hauslehrer. I would be employed by the parents or invited by teachers because the children were impossible and I had a way to play a little ‚Aichhorn‘ and to learn that sometimes one can only win people over if one deceives them better than they can deceive. As a matter of fact, my first big idea was to work not only with neurotic children, like Anna did, but with children who were delinquent and psychotic and that’s what I developed in Topeka. One would need to re-read Wayward Youth its now in English. I just wish it would have more influence in America. Aichhorn looked so unbelievably seductive. You wouldn’t believe that he could out-do you any time.

So this was my training in psychoanalytic pedagogy. Willi Hoffer was my first teacher of psychoanalytic pedagogy. I met him again in England and he was, for me, for a while, the God. He was married to Hedwig and I used to go in the inner city in Vienna to see him. And remember Anna Freud, before she became an analyst, really wanted to be a teacher. She wanted to be a pedagogue. And she was one of those people who developed psychoanalytic pedagogy. And Anna had a way about her. One sort of instantly fall in love with her. Where she goes, I go. But you know, if you understand the hint, she was really untouchable, because she was a true Freudian. She tried to develop what her father did and she never married. So that all of us had a fantasy – Anna, Anna, Anna. So while none of us got Anna, we all became Freudians – Anna Freudians!

So from Anna Freud I learned that if you want to teach, you must understand the child, not just the subject. So I started to go to the Institute and very soon found out that in order to make use of psychoanalysis one has to understand oneself. One ought to be analyzed. You must remember that was a time, I was twenty two years old, when it went a little faster there than it goes here, before one is accepted by an Institute. Well, Anna advised me to be analyzed by a doctor whose name was Kronengold, who later, when he came to America, shortened the name and americanized it to Kronold. You know in America we take big things and make something small and quick out of them.

So that was Kronengold and I went to him. Kronengold was a Jewish person who had come from Poland in order to be an analyst. And I’m not quite sure if he, at that time, was a training analyst but, in any case, I could go to him.

Then when the country was invaded, I came to my hour with the feeling that nothing can happen to me even though the country is now fascist, because I have an analyst! He will protect me. Its a nice pleasant transference but it was a transference that did not hold with reality, as we all know. Whenever we remember our own transference experiences we realize that these transference experiences are not the complete measure of reality. So when I came to my hour he said to me, „This will be our last hour because I will escape today to Poland and I can only advise you escape as quick as you can.“ He let me go. I can’t go to Poland. What do I do there? I don’t understand that language. And in addition I sensed already Poland won’t last very long either before the war will come and the fascists will take over.

So, he couldn’t protect me. When the fascists came I had tried to fight against them. I was a young man. I was at that time a member of the Viennese Socialist Party and I still am a member. I go back there and pay my dues every year. I just don’t tell it to the police in America. Well, I distributed leaflets when the parliament was closed. The fascists had taken over. That was under Dollfuss – before Hitler. I distributed leaflets – OPEN THE PARLIAMENT – OPEN THE PARLIAMENT – and on the street the police stopped me and found the leaflets in my pocket. Austrian prison! But fortunately I got out of it and said somebody gave it to me or whatever it was so I just spent a couple of weeks in prison. So Kronengold said, „You better get going and run.“ And he went east, back to Poland and I went west, to England. I had been in lectures by Bernfeld, I took lectures with Friedjung and Paul Federn and all the others and you sort of got an idea how the European world of psychoanalysis and all these unbelievably creative people – fell apart. They were on the march but the march was to escape.

DB: I saw a picture in a book of the Nazi book burnings and a list of all the banned psychoanalytic books. I remember it specifically included some of Bernfeld’s books too.

RE: Yah, they all started to burn all the books that were not Hitler books and I find it hard to confess that I took some of the books, that I knew would be dangerous if the Nazis had found them in my home, and burned them. Others I didn’t burn. I sent them by mail to England and found them there again. So you see the Nazis weren’t the only ones that burned books. It had started when I took the Interpretation of Dreams, the first edition, And I said. „I will not let them burn it.“ and I smuggled the books across the frontier. But I was also smuggling Karl Marx’s Kapital, the Communist Manifesto, and all the forbidden left wing library. For the Nazis, Freud was just a seducer of the people. Fortunately some stupid soldier, who had to go through my luggage, didn’t know what it was. Maybe he was looking for apples and food, you know, or money. Now some of these books are here in this library – books that I got as gifts as a young man. In 1938 came the invasion. A few weeks later Freud left and was saved and then a few weeks after that I escaped and went to England. In England, of course, I saw Anna Freud but not Sigmund Freud because by that time he was a dying man. In 1939 he died after many many surgeries for cancer of his mouth. I came then as a refugee to England and there I found no difficulty because in England there were, in a way, two schools. Where can I go? and where can I join? And for the first time I clearly saw the split among the analysts and I would run and go to listen to Anna Freud and then I would also listen to Melanie Klein. I learned from her and I learned from Anna. Of course, at that time, I knew where I belonged. It took then a while before you could read and understand Melanie Klein and say „Well the world is bigger than Anna Freud.“ In England I was for a few months going to these lectures, courses and so on.

The question now was „How will I get back to analytic training?“ So I emigrated to the United States and went to Cambridge to complete the analysis that I had started with Kronengold earlier. I was analyzed by Edward Hitchmann, who was a student of Freud. He told me an interesting story. You know in those days, they were much more traditional. He would go up to Bergasse to meet Freud and then he would go with Freud around Ringstrasse. And they would walk around Ringstrasse while talking to each other for some of the analysis. I don’t know if you had an analyst who took you for a walk and analyzed you, but what I’m trying to say is that we sometimes believe so much in orthodoxy that we forget that our really orthodox teachers were not really that orthodox. I could not check out if it was a good analysis or whether they should have remained in Bergasse. Here is his picture that he signed for me.

DB: (reading the inscription on the photo of Edward Hitchmann) „To my eminently successful pupil Dr. Rudolf Ekstein, with warmest wishes for he future.“

RE: And of course it was a pleasure to be recognized as his student in this way. Now in order to get the job that I wanted I had to become a case worker. I realized that psychoanalysis for me at that time would be impossible – nothing doing! The Americans had become very hostile to lay analysis at that time. Now maybe a man like Kris could survive but not a young man like me? So I decided that if I wanted to stay with the notion of helping people I will go and become a social worker. I went to Boston University and after the doctors degree in Vienna, I got a masters degree and then I came to Los Angeles and an organization gave me an honorary Bachelors degree so I had a complete American education and then I went back to Vienna and got from Vienna, 50 years later, an honorary medical degree!

DB: So you had your Ph.D. in philosophy and got a Master’s degree in Social work and then where did you go?

RE: I started in Brooklyn in New York but the New York Institute did not permit me to teach. Hartmann was there. And when you think of modern psychoanalysis you cannot help but think of Heinz Hartmann. Ego psychology, I realized at that time, was not only in a new world but was also in a world different from the psychoanalysis of 1900 or 1895 and in the life of Freud. Who would have thought in 1900 that a few years later, about 1923, there would be ego, superego and id. It was a completely different notion of the human mind. And Heinz Hartmann, at that time, signed this picture for me and when I got that and he signed it that way – I felt, I am a part of them.

DB: (reading the inscription) „To R. Ekstein, affectionately Heinz Hartmann.“

RE: Here is another one of those pictures that one treasures. Theodore Reik. You see he signed it.

DB: (reading the inscription) Yes! „To Dr. and Mrs. Rudolf Ekstein, cordially Theodore Reik. X-Mas 1959“.

RE: I met him in New York. Theodore Reik was an interesting person. Of him, you would have to say that he was not a joiner. He could not join the New York Society. He had to lead a group of his own. And maybe its the trouble with all of us, we want to be a part of a group and belong and at the same time we have something unique. So when you then write a book like „Listening with the Third Ear“ well it should be something special and very different and so Theodore Reik was then alone. He had his own group. I have a few friends now who at the time studied with him and became Reikians.

DB: Yes but what happened to you?

RE: Now what happened to me was that I had published a psychoanalytic paper, and in response, I got a letter from a person whom I had never met and I had no idea of who he was. His name was Karl Menninger and he was from Topeka and I must confess I had no idea what is „Topeka“ and I had no idea what is „Kansas.“ And he said he would like to have me there as a training analyst.

In Brooklyn and New York I did therapy. I saw patients. I taught at the University and did all kinds of things but to be a training analyst? and a lay analyst? what more could one possibly wish? And David Rapaport interviewed me in New York and I came then to Topeka and was interviewed by people like Robert Knight, who unfortunately did not stay long enough. And one of my disappointments was that the moment I came to Topeka I thought „Now I am finally settled in an analytic environment.“ and then Robert Knight left for Stockbridge. Nobody had told me. What kind of a place can that be? What reasons did he have? of course, he gave me no reasons and we saw now a second emigration. The first from New York to Topeka, then from Topeka to Stockbridge – a number of marvelous people. Bob Wallerstein was a student of mine at Menninger’s and you may know The Teaching and Learning of Psychotherapy 1958, is a book we wrote together. At Karl Menninger’s Topeka I began to write books and became slowly Rudi Ekstein. It takes a long time to become a Rudolf Ekstein. But when I saw so many people leaving Topeka, leaving one after the other, I couldn’t stand it anymore. I wanted a home where one could stay for good. I also thought „What will my children do? Will they go to school in Topeka?“ I couldn’t quite imagine it. Meanwhile some of my publications were known so I got an invitation to come to Los Angeles to join a clinic. I accepted the offer and left.

I wanted to do research and teach, not just have a private practice, and so I came to Los Angeles. ((Siehe hierzu vertiefend: Roland Kaufhold (2001): Bettelheim, Ekstein, Federn: Impulse für die psychoanalytisch-pädagogische Bewegung. Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen 2001. Dorothea Oberläuter (1985): Rudolf Ekstein – Leben und Werk. Kontinuität und Wandel in der Lebensgeschichte eines Psychoanalytikers. Geyer-Edition, Wien 1985.))

This was here in Los Angeles (pointing out a picture of a group of four people) and what you find here is a fantastic group – Greta Rubin is an analyst, Polish refugee; Rudi Ekstein analyst, Austria; Anna Freud, Austria; Miriam Williams, I think Poland; and Rocco Motto, the American with an Italian background. So it really was a European world and Anna came to lecture in Los Angeles and, of course, this is one of those moments when one feels – home again! Motto was the one American. He had the Reiss-Davis Clinic of which he was the Chief and he had an interesting way of running that clinic. He got himself Europeans to teach there or to do therapy there and for a while we had a wonderful school until the Board of Directors felt it didn’t make enough money and the school ended, unfortunately – but so true.(Pointing to himself in the picture next to Anna Freud) Would I love to know what did Rudi think at that moment. Well I do know. There are many ways in which one can be in love with someone. My wife will forgive me when I say „Forever after in love with Anna Freud.“ But in a different way, namely I want to learn from her and be what she is.

Hans Jokl came later to Los Angeles so we had again some Viennese there and such it goes. Martin Grotjahn was here in Los Angeles. He was not an easy man. He was against lay analysts so when I met him in Los Angeles he said to me „As you know I am against lay analysis but with you I make an exception.“ Now, of course, I have an Austrian mouth so I said „You know I am against medical analysis but with you I make an exception.“ and we became friends. He objected to lay people but when he met me he said „We accept you but one or two like you is enough“.

DB: I have some pictures here of some of the European émigrés associated with the San Francisco psychoanalytic community. Here is Edith Buxbaum whom you said supervised your work in Vienna. She was affiliated with the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute but practiced in Washington state.

RE: Yah, Edith Buxbaum was important for me. She settled in Seattle and was both a child and an adult analyst. She was a very powerful lady for me because she, like I at that time, started as a pedagogue, as a teacher.

DB: Did you know Anna Maenchen?

RE: Yah, and when I see Anna Maenchen I cannot help but remember the days when I started psychoanalytic pedagogy back in Vienna and she was, at that time, one of my teachers.

DB: What about Emanuel Windholz? Did you know him?

RE: Yah, Windholz. He would say to me „Well I’m not really for lay analysis but you are an accepted piece of the old world.“ Karl Menninger made a place for lay analysis. Windholz tried that too but when Bernfeld started his own private training, he seemed to become an external threat and difficulties arose between Bernfeld and Windholz. The Windholz that I remember had no difficulty to make an exception with me. But I realized that analysts, wherever they are, as good as they are at understanding people and helping people, have not yet learned all that they need to know when it comes to understanding each other. So that we find almost everywhere the different schools of analysis with their different struggles for power and I never know are these struggles for power or are they different ways of thinking?

DB: Erik Erikson was a lay analyst as well. Did you know him?

RE: The one recollection of Erik Erikson that I have is that I gave a paper on Picasso and Erikson came to discuss it and I published the paper with all the changes that Erikson helped me to make and to see more than I saw before.

DB: How about Bruno Bettelheim?

RE: Bruno. I don’t know if you know that he was in a concentration camp and Mrs. Roosevelt helped him to get out. When he came to America he wanted to do something to create a school for delinquent children, for sick children, and created it as a positive concentration camp. At the Orthogenic School the children could not leave. Their parents had to be obligated to leave the children there. They were, if you like, in prison. Bettelheim had a way to help people to be restored and he concentrated on their welfare so that they could get out. I had a rough time with Bruno because occasionally I came to Chicago to teach there and he believed its the environment that changes the child while I believe its the psychotherapy that changes the child. I developed more and more child psychotherapy and child analysis in Topeka while he believed its the environment that does it. We had a long friendly battle until we found out that the work of each has a place in the work of the other. Bettelheim lived his last years in Los Angeles and we met very often and, of course, I have contact with one of his daughters.

DB: Did you ever see Bernfeld again in the United States?

RE: I met Bernfeld a couple of times in America but by that time he was an older man. I was deeply impressed when I saw the aged face and the illness and the tiredness. My visit meant a lot to him. I was, at that time, in Topeka and Bernfeld, in the beginning, had visited in Topeka so he knew from where I was coming. I was, for him, one of the much younger people that came from the old world. He had by that time given up much hope in psychoanalysis having a future and, the way I sensed it at the time, he really seemed to say to me „Do I, Siegfried Bernfeld, have a future?“ He had become a pessimistic man. He was somebody who once in earlier days seemed to me a hero to follow – the one with whom you are willing to march wherever he goes. But by that time, in San Francisco, he seemed to me to be a pessimistic man. ((Siehe hierzu vertiefend: Roland Kaufhold (Hg.) (1993): Zur Geschichte und Aktualität der Psychoanalytischen Pädagogik: Fragen an Rudolf Ekstein und Ernst Federn. In Roland Kaufhold (Hg.) (1993): Pioniere der Psychoanalytischen Pädagogik: Bruno Bettelheim, Rudolf Ekstein, Ernst Federn und Siegfried Bernfeld, psychosozial Nr. 53 (1/93), S. 9-19. https://www.hagalil.com/2010/04/10/interview-federn-ekstein/))

I saw him once or twice and I was also very much occupied in a good many of my writings with the thoughts of Bernfeld, particularly the ones on education. I came back to Vienna many years later, in better days, with a paper about Bernfeld. So he had been a hero to follow and then in later days I realized, maybe I have to go alone.

If you want to do something yourself, you don’t have to push away the heroes and argue against this and become an anti-Bernfeldian or anti-Freudian. I built on the heritage they gave me and it helped me to continue. When Bernfeld was in San Francisco, he isolated himself more and more from the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Society because that they did not want to accept, at the time, his wife since she was a lay analyst and for them she was not competent enough. For Bernfeld, it was just the lay issue. He withdrew and started his own group. So in the end he was an isolated man except that he remained in the minds of those of us who came from the past. So for me, he is not isolated because he is in me. For Windholz, it was a different story because there was the medical issue and the lay issue. It is very hard to say to what degree did Bernfeld defend the wife and to what degree did he defend a lay analyst (vgl. Benveniste, D. 1992). ((Siehe hierzu vertiefend: Daniel Benveniste (1992): Siegfried Bernfeld in San Francisco. Ein Gespräch mit Nathan Adler. In: Karl Fallend und Johannes Reichmayr (Hg.) (1992): Siegfried Bernfeld oder Die Grenzen der Psychoanalyse. Materialien zu Leben und Werk. Stroemfeld/Nexus: Frankfurt a. M. 1992. www.hagalil.com/2010/10/18/bernfeld-2/))

It is also true that he became, in the end, a man who left the original creative ideas of education and became an historian along with his wife Suzanne. They went back to Freud and wanted to describe the phases of Freud’s life. It was, how shall I put it, if I have no place in the new world to be happy, I now go to the old world. It would be as if you say today, „Who cares, I want to study philosophy in the 17th century.“ And then you lose yourself in the past and more and more get isolated. I saw him once more. He was quite ill at the time and I was asked to see him only briefly. And so it went.

In the end Bernfeld left the analytic society and had a group of psychologists of his own. Then came slowly the end. And he left the place that didn’t accept him anymore. He tried to create a place that couldn’t begin anew. Occasionally one hears about the one or the other who was at that time a part of that new group.

DB: Yes, my clinical supervisor and mentor was a member of that group.

RE: Yah, what was his name?

DB: Nathan Adler.

RE: Yah, it sounds familiar. When I was trained it felt to me like, I have now a family. You know, I came out of the socialist movement destroyed by fascism. One is alone literally, you know, with a backpack. Alone, I mean, in the sense of – who thinks like I do? I had the good luck once to listen to Anna Freud, to Schlick and I knew I had found my intellectual family. And when I look at these societies now, as they exist, all I hear is „How much are you making? Did you buy yourself a new house? Did you finally get a way from the Valley and get a house up in the hills?“ Endless! And I realized, they are Americans, they cannot help it. They grew up with ideals such as Rockefeller and Ford. You know even the good presidents were well to do rich people. Where are the days of Abraham Lincoln?

One of the tragedies of America is that its a pragmatic culture. Its not interested in its history. But when you’re an analyst you cannot be pragmatic unless all you want to do is ask, „How much will I make today?“ I don’t ask at the end of the day „How much did I make?“ But as you see I live quite comfortably.

So we are sitting here and you say „Look at this room!“ and you ask yourself „Is this America?“ This is America because every American that really understands this country, returns also to his past. The philosopher said, „Those who don’t remember their past are condemned to repeat it.“ We want to remember the past and live in the present and work for the change of the future The past is what you inherited but you make it useful for other people so that it is not private property alone.

I think of my last conversation with Bruno Bettelheim, just here on this sofa. We spoke about our teachers who helped us become different and to become contributors.

There may be Americans who have difficulties to accept new people that come from other countries. They say „Enough, we don’t want them.“ But there are also Americans who understand and remember even though they themselves were born here. Their parents or their grandparents came from somewhere. Its a land of unlimited opportunities that you ought to keep open. I think of psychoanalysis as an opportunity. One’s own analysis, does not serve the purpose to take away a headache or take away a symptom, it goes much deeper. It helps a person to discover the repressed and to become another person.

Willi Hoffer who was my ideal teacher was the very best friend of Bernfeld. After the first world war they had created a home for wayward youth, like Aichhorn. They had a different home, mainly to deal with refugee children after the first world war – Polish Jewish children and other children that came there. It is important to remember that the analytic teachers at that time were socially involved. They didn’t just have a private practice to make money or to cure a few people. They were socially involved.

They were engaged in research and all of them are known in the literature. While we have today an endless number of people for whom the praxis is enough, I would like to hope that people like me could push a few little people into new opportunities and to do more than a practice or work in a hospital and be only a practitioner. I don’t mind practitioners, but I’d like those who can go beyond that to have the opportunity to do so.

And I would like to have psychoanalytic institutes that go beyond training practitioners. When one looks at the membership list of the Viennese psychoanalytic society, before it all fell apart, there were about 70 people – a small group. You go through the list, name after name and find out what they contributed and you can find it in this room – unbelievable! (Dr. Ekstein points to his massive collection of books on the wall.) You take 70 members from this town or another town and ask yourself „Where is their work?“ What is the relationship between creative contributions of the society and the number ofgraduates from that group.

DB: Where do you see yourself in relation to the Institute?

RE: I am half outside, half inside. Its a little bit like a love affair you know. You have a person in your arms and it feels suddenly the two of you are one. But how often does that happen? How often does it happen that we suddenly feel alone? The same is with Institutes. Sometimes one feels its a lovely love affair and sometimes one thinks „Oh heck, I got screwed again!“ ………… I never spoke this way in Vienna. I learned this in America.

Its so interesting you know how a group can sort of fall apart. Some go here, some go there before they again find connections. In this way the analysts all of a sudden have been able to have an International Psychoanalytical Association and that, by the way, was for me very important. Because when I was a young man, an adolescent , one of the most important songs was ‚Die Internationale Siewird Die Menschhert Sein.‘ It was a Socialist song that said a day will come when we won’t be nationalistic anymore. All people, all over the world will create one unity, in one Association Internationale. But even that didn’t last because there was the First International Working Men’s Association and then the Second and then the Third, when the Communists became powerful, they had their own Internationale. We thought „You’re just like Hitler. Dictatorship.“ And such it goes and with the analysts it was a little bit like that. Are you in a Jungian group?

Are you in a Freudian group? Are you in a Kleinian group? To what group do you belong? And can you slowly learn, like I tried to learn, the language of each group. If I want to marry my wife I’ve got to know English and if she wants to be married to me, and I want to show her sometimes Vienna, she better learn a little German. But then she originally spoke Greek so „Can I remember a little Greek that I learned?“ And we need to create bridges between psychoanalytic languages just as we build bridges between other languages.

DB: Dr. Ekstein, you were a young man when you were studying psychoanalysis in Vienna and Freud was an old man but I am curious to know if you ever saw him.

RE: Freud was not at that time teaching anymore. But I happened to have a friend with whom I studied philosophy and he lived directly across from Bergasse 19, in Bergasse 20. One of his brothers was a Communist Party member and once they came to arrest him and so I got arrested too, so what else is new? But while studying for the Rigorosum (final exams) we would sometimes see Freud at the window and all of a sudden the whole Rigorosum became unimportant. I envied my friend for that window!

After Freud had escaped, the Nazis found it important to put a swastika on his home. I will tell you, I go there each year. There is a museum – no more swastika – but in the museum they have a picture of the swastika over the door. I would like to say that in order to understand the resent one must allow oneself to have a past. Those who do not remember their past are condemned to repeat it. Sometimes I cry when I remember my past, but I will not repeat it. I’m an American and a Viennese citizen.

Dieser Beitrag von Daniel Benveniste (1998) – A Bridge Between Psychoanalytic Worlds: A Dialogue with Rudolf Ekstein – ist zuvor erschienen in The Psychoanalytic Review. 85 (5), New York. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Themenschwerpunkt Rudolf Ekstein

About the author

Dr. Daniel Benveniste is a clinical psychologist with extensive experience treating adults, couples, adolescents and children. Daniel Benveniste received his training in the San Francisco Bay Area and worked there for many years. He did his undergraduate and graduate clinical psychology training at San Francisco State University and earned his Ph.D. in clinical psychology at the California School of Professional Psychology – Alameda Campus. In San Francisco he maintained a private practice in which he worked with adults, couples, adolescents, children and families seeking psychotherapeutic assistance for a wide variety of problems. For over 25 years, he also managed to devote some of his time to community service.

From 1999 through 2010, he maintained a private practice in Caracas, Venezuela and taught graduate students at Universidad Central de Venezuela and Universidad Católica Andres Bello. He also participated in the Red de Apoyo Psicologico (Psychological Help Network) by providing trainings in crisis intervention following the massive Venezuelan floods of 1999 and subsequently directing an investigative treatment program for a small group of children directly affected by the disaster. Later, when there developed dangerous levels of social ‘hysteria’ (panic) associated with the Venezuelan National Strike (Dec. 2002 – Jan. 2003) and other periods of intense social unrest, he wrote articles and gave lectures and trainings on distinguishing panic from fear, and developing coping strategies in the midst of high anxiety.

Wir bedanken uns bei Daniel Benveniste für die Nachdruckgenehmigung seines Interviews mit Rudolf Ekstein sowie für seine zahlreichen Anregungen zum Leben und Werk Rudolf Ekstein in den Jahren von 2005–2012.

Deutschsprachige Beiträge von Daniel Benveniste:

Daniel Benveniste: Siegfried Bernfeld in San Francisco. Ein Gespräch mit Nathan Adler. In Karl Fallend und Johannes Reichmayr (Hrsg,): Siegfried Bernfeld oder Die Grenzen der Psychoanalyse. Materialien zu Leben und Werk. Stroemfeld/Nexus: Frankfurt a. M. 1992, 368 S.

https://www.hagalil.com/2010/10/18/bernfeld-2/

http://www.werkblatt.at/fallend/bernfeld.htm

http://internationalpsychoanalysis.net/2011/05/07/forgotton-analysts-siegfried-bernfeld-at-sf-apsaa-meetings/

http://www.edithbuxbaum.com/HamidaBosmajian.html

http://www.edithbuxbaum.com/ROLAND.html

Ergänzende Nachbemerkung von Roland Kaufhold:

Nach Rudolf Eksteins Tod habe ich mehrere erinnernde Nachrufe auf Rudolf Ekstein verfasst. Hierzu nahm ich auch Kontakt mit dem seinerzeit in Venezuela lebenden amerikanischen Psychoanalytiker Daniel Benveniste auf. Ich wusste von seiner Freundschaft mit Rudolf Ekstein. Daniel Benveniste vertraute mir zahlreiche private Fotos für meine Publikationen über Ekstein an, und am 31.3.2005 schickte er mir drei persönliche Anekdoten, die die Persönlichkeit Ekstein veranschaulichen. Ich habe sie in meinen Nachrufen eingearbeitet und möchte sie an dieser Stelle noch einmal wiedergeben:

“The first time I encountered Dr. Ekstein was at a conference where a number of leading clinicians were speaking about schizophrenia and psychoanalysis. The conference had not yet begun when I noticed, from my seat on the center aisle, a short distinguished looking older man with long silver hair wearing a fine suit and with wisdom and experience chiseled into his dramatic facial features. I knew at once, this was the famous Rudolf Ekstein, though I’d previously only seen him in pictures. As he walked down the aisle in my direction, I felt a rush of excitement that I tried to conceal. Suddenly he stopped in front of me and asked in that marvelous Viennese accent, „Do I know you?“ I replied, „No, I don’t believe we’ve met.“ (As if it were possible I might have forgotten). And then he said, „Vell, are you a Kleenical Psycholojeest?“ I said „Yes.“ to which he replied, with a sigh of recognition, „Ahh, yes! We all have that look, don’t we?“

Some years later I contacted him and asked if I could collect his oral history on his early training in Vienna. He readily agreed and we set a date to meet. I flew from San Francisco, where I was living, to his home in Los Angeles. He greeted me at the door with a flourish and then ushered me into his home which was a veritable psychoanalytic museum filled with old books, old photos, old letters, mountains of Freudiana and artifacts of his own illustrious psychoanalytic career including countless diplomas, certificates and honorary degrees, framed and covering the walls. After receiving the tour we took a walk to a nearby restaurant and were about to order lunch. I looked at the menu and decided on something. The waitress arrived to take our order and Rudi asked me “What will you have?” I said, “I’ll have the pasta primavera.” Rudi turned to the waitress and said, “I’ll have the same.” He then turned to me and added, “It will foster the identification!”

In 1995 I brought Rudi and his wife to San Francisco where he delivered a public lecture on his reminiscences of psychoanalysis in Vienna. There were three other speakers in the symposium, which I had organized, and I prepared signs in the parking lot to reserve spaces for their cars. At the end of the event I asked my friend and colleague, Dr. Jeff Sandler, if he could give the Ekstein’s a ride to their hotel. He readily agreed and afterward told me that on their way out of the parking lot Rudi saw the sign again that read “This Space Reserved for Rudolf Ekstein” and he asked Jeff to stop and take the sign for him. Rudi’s wife, exasperated with him, cried out, “Rudi! Where are you going to put a thing like that? (Remember his house is full of diplomas and honorary degrees.) Rudi paused a moment and said, “Over my bed!”

Bob and Judy Wallerstein could tell you quite a bit about Rudi as they have known him ever since they were all working together at Menningers.

There is also a nice biographical sketch and clinical discussion with Rudi that appeared in Virginia Hunter’s book Psychoanalysts Talk, The Guilford Press, 1994.”

Von 1999 – 2010 lebte Daniel Benveniste in Caracas, Venezuela; aus politischen Gründen musste er Venezuela verlassen und siedelte 2010 nach Bellevue, Washington über. Am 15.1.2012 schrieb er mir per e-mail:

„Thank you for your letter and for reminding me of Rudi’s centennial. I would be delighted if you republished my Rudolf Ekstein interview. The political, social and economic situation deteriorated in Venezuela so we left in September 2010 and we now live in the Pacific Northwest of the United States in Bellevue, Washington.” Und am 23.1.2012 fügte er ergänzend hinzu: “It looks like you are going to be able to make a very nice centennial salute to Rudolf Ekstein and I am pleased that you have enabled me to be a part of it.”

Nachrufe auf Rudolf Ekstein:

Roland Kaufhold (2005a): „… denn es ist ja die Beziehung, die heilt.“ Erinnerungen an den psychoanalytischen Pädagogen Rudolf Ekstein (9.2.1912 – 18.3.2005), in: Kinderanalyse, 13. Jg., H. 3/2005, S. 341-347.

Roland Kaufhold (2005b): „Wiener mit amerikanischem Pass“. Erinnerungen an Rudolf Ekstein (9.2.1912 – 18.3.2005). In: TRIBÜNE. Zeitschrift zum Verständnis des Judentums, 44. Jahrgang, H. 174, 2/2005, S. 92-96.

Roland Kaufhold (2005c): „Ich bin ein Wiener mit einem amerikanischen Pass!“. Erinnerungen an Rudolf Ekstein (9.2.1912 – 18.3.2005), in: psychosozial, 28. Jg., Nr. 101, Heft III/ 2005, S. 129-133.

Roland Kaufhold (2008): Rudolf Ekstein (1912 – 2005): „Wiener mit amerikanischem Pass“. Vor 70 Jahren, am 22.12.1938, floh der Wiener Psychoanalytiker und Pädagoge Rudolf Ekstein in die USA, haGalil https://www.hagalil.com/2008/12/ekstein.htm