|

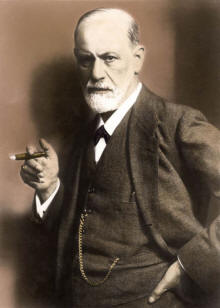

70 years ago:

Sigmund Freud's Journey into Exile

|

"The Jews (...) have

seized upon my person from all sides and all places with enthusiasm, as

though I were a God-fearing great rabbi. I have nothing against it, after I

have clarified my position toward faith unequivocally."

Sigmund Freud to Arthur Schnitzler, May 24, 1926

"What progress we are making. (...) In the Middle Ages they

would have burnt me; nowadays they are content with burning my books."

Sigmund

Freud, 1933 |

Foto: © Archive S. Fischer Verlag

|

by Roland Kaufhold / Hans-Jürgen Wirth

[Deutsch]

Sigmund Freud was born 150 years ago, on May 6, 1856, in

Moravia. He went to school in Vienna, and in Vienna he developed

psychoanalysis, as a collaborative effort with numerous colleagues, almost

all of them Jews. Freud was a thoroughly sceptical man, not a

philanthropist, and occasionally he used the term "riffraff" when thinking

of people in his environment, who were mostly hostile towards him. He did

not have any illusions about the destructiveness inherent in human beings.

He was always aware of the possibility of human self-destruction. Filled

with apprehension, Freud wrote on the eve of the National Socialist "seizure

of power", at the end of his great work Civilization

and Its Discontents:

"The fateful

question for the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent

their cultural development will succeed in mastering the disturbance of

their communal life by the human instinct of aggression and

self-destruction. (...) Men have gained control over the forces of nature to

such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty in

exterminating one another to the last man. They know this, and hence comes a

large part of their current unrest, their unhappiness and their mood of

anxiety."

It was with

the greatest reluctance that at the age of 82 Freud started his journey into

exile. Between 1932 and 1938, almost all Viennese psychoanalysts went into

exile or were forced to do so, except Freud. The cancer-stricken old man,

being too optimistic, misjudged the danger and longevity of National

Socialism, as did many intellectuals in those days. Moreover, the seriously

ill man may be justified in assuming that it would be possible for him "to

die undisturbed and in peace" in his hometown.

What follows

is a description of Sigmund Freud's journey into exile in Great Britain,

where he died 15 months later at the age of 83, on September 23, 1939.

A "godless Jew"

In 1918, towards the end of World War I, Freud described

himself as a "godless Jew" in a letter to the Swiss pastor and psychoanalyst

Oskar Pfister. Ten years before he had written to the very same pastor: "Quite by the way, why did none of the devout create

psychoanalysis? Why did one have to wait for a completely godless Jew?"

As a

determined atheist, Freud did not believe in the existence of a god as a

source of comfort for our spiritual life. He viewed the latter as an

illusion. He had a passionate cognitive interest in truths that could be

unpleasant for us, the truth of the abysmal depths of human inner life,

including our capacity for the most extreme destructiveness.

Early on

Freud was aware of his identity as a Jew – it was forced upon him by his

predominantly Catholic environment. In his letters he spoke again and again

of his Jewish belongingness – an identity that increasingly turned to an

attitude of proud defiance.

Vienna had

become a place of refuge for Jews in the second half of the nineteenth

century. In 1880 – Freud had just published his first medical writings, 15

years prior to his first great psychoanalytic work Studies on Hysteria

– ten per cent of all Viennese inhabitants were Jews. "By the

1880s, at least half of all Viennese journalists, physicians, and lawyers

were Jews", wrote Peter Gay in his monumental Freud biography.

When Freud attended the Gymnasium (secondary school) from 1865 to1873

in Vienna, the number of his Jewish fellow pupils rose from 44 to 73 per

cent.

Early on he

felt that his disturbing, pioneering discoveries were opposed by society

both out of unconscious and anti-Semitic motives. During a walk, his father

told the ten or twelve year-old boy of an anti-Semitic episode where a

Christian had knocked his cap off his head while shouting: „Jew, off the

sidewalk!", and his father had obviously tolerated this attack without

resisting. Young Sigmund was shocked and outraged that his father had chosen

to withdraw. His father's submissiveness "did not seem heroic"

to him, as he wrote in his Interpretation of Dreams (1900). His

father's retreat triggered revengeful fantasies in the young boy who rather

identified himself with the fearless, combative Semite Hannibal.

As of the

year 1895, Sigmund Freud attached in his writings fundamental importance to

human sexuality which was tabooed in those days. This provoked fierce

counter-reactions in his thoroughly Catholic hometown Vienna. In 1896, as an

answer to Freud's study on hysteria, which had just been published, the

psychiatrist Rieger wrote for example, that Freud's views were so absurd

that no mad-doctor could read them without really feeling horrified.

Freud had the feeling of being socially ostracized.

A Jew who

wanted to secure an academic career in Vienna only succeeded when he was

able to overcome obstinate obstacles. Yet, his realistic assessment did not

have the effect that Freud would have tried to assimilate or to deny his

Jewish roots. In 1897, at the age of 41, he instead joined the Viennese

Lodge B'nai B'rith and held lectures there. With a personal warmth that

was quite unusual for him, Freud expressed the feeling of belongingness to

this Jewish association several times.

In his

well-known autobiographical writing, An Autobiographical Study,

published in 1914, Freud already marked his viewpoint with absolute, perhaps

somewhat stylized clarity: "My parents were Jews." And Freud added: "I, too,

have remained a Jew".

"Because I was a Jew, I found myself free from many prejudices which limited

others in the employment of their intellects, and as a Jew I was prepared to

go into opposition",

and to waive the agreement of the compact majority.

On May 8,

1926, B'nai B'rith celebrated Freud's seventieth birthday in the form of a

festive meeting and honoured its prominent member with a special edition of

its "Newsletter".

In his

address to the B'nai B'rith – which had to be read by a fellow member

because Freud was ill – Freud recalled the circumstances under which he had

joined this Jewish association 30 years ago, stating that this was "my first

audience". In the years following 1895, two strong impressions seemed to

have the same impact on him. On the one hand, he gained first insights into

the depths of the human drives, saw quite a few things which could have had

a sobering effect, at first even be horrifying; on the other hand, the

announcement of his unpleasant discoveries had the success that he had lost

most of his previous interpersonal relationships; he felt "as though

ostracized", as shunned by everybody. In this state of isolation, he

recalled, the longing for a "select circle" of highly spirited men arose in

him, a group that would welcome him "regardless of my audacity".

And he was told that this association was a place where such men could be

found.

"That you are

Jews could only be welcome to me, for I was a Jew myself, and it had always

seemed to me not only undignified, but quite nonsensical, to deny it"

|

Foto: © Archive S. Fischer Verlag

|

To avoid that

his new science of psychoanalysis be perceived by the mostly non-Jewish

public as a "Jewish" cognitive and treatment method, Freud consciously made

some concessions in his society-specific politics

when establishing his Psychoanalytic Society: He tried to

make sure that the psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung – the "Aryan" – who had

contacted him in 1906, would be given a leading position within his Viennese

Psychoanalytic Society. For several years, Freud even considered Jung as his

"crown prince", referring to him occasionally even as "his son". In letters

to his Jewish colleague Karl Abraham, Freud explained in 1908 that it would

psychologically be so much harder for Jung "as a Christian and the son of a

pastor"

than for his Jewish colleagues to overcome inner resistances against

psychoanalysis. Referring to Jung, he added: Hence, "his adherence is all

the more valuable. I almost said that only his appearance has saved

psychoanalysis from the danger of becoming a Jewish national concern."

In the same year, he wrote to Abraham: "Be assured, if my name were

Oberhuber, my innovations would have found, despite it all, far less

resistance."

And: "Our Aryan comrades are, after all, quite indispensable to us;

otherwise psychoanalysis would fall victim to anti-Semitism. (…) We must, as

Jews, if we want to join in anywhere, develop a bit of masochism," even be

prepared to hold still for a measure of injustice.

When Jung want his separate way a few years later, this was a trauma in the

history of psychoanalysis. It must be added that as of the year 1933, C. G.

Jung did not even refrain from introducing a clear distinction between the

"Jewish and the Aryan Unconscious" in his psychological writings.

In the

mid-1920s – Freud had published a large part of his writings, had won an

impressive group of supporters and had gained international recognition by

then – the signs of anti-Semitism became more obvious. In 1927, the liberal

Freud called for the backing of the Socialist Party. He emphasized his

belongingness to the Jewish people, to his Jewish roots now more and more

emphatically.

In an

interview in 1926, the 70 year-old Freud said: "My language is German. My

culture, my attainments are German. I considered myself German

intellectually, until I noticed the growth of anti-Semitic prejudice in

Germany and German Austria."

And in 1935, Freud wrote in a letter, "that I have always held faithfully to

our people, and never pretended to be anything but what I am: a Jew from

Moravia whose parents come from Austrian Galicia".

In 1932, the

first Viennese analysts fled into exile – a process which reached its sad

peak in the years 1937 and 1938. Freud's deeply ambivalent assessment of the

threat which his very existence was exposed to, was reflected in his vivid

correspondence in the 1930s. In March 1933, he wrote to Marie Bonaparte –

who would support his emigration to London five years later – that one

should not overlook that the persecution of Jews and the restrictions on

intellectual freedom were the only items of Hitler's programme which were

feasible. Anything else would be nothing but phrase and utopia. He added

that the world was a big jail and Germany the worst cell. And in Germany,

Freud anticipated a paradoxical surprise. There they started with a deadly

hostility against Bolshevism, he wrote, and they would end with something

which would ultimately not be distinguishable from it. Except perhaps for

one thing, he added, namely that Bolshevism had adopted still revolutionary

ideals, but Hitlerism only medieval-reactionary ones.

And when his

books were publicly burned in May 1933, he quipped sarcastically: "What

progress we are making. (...) In the Middle Ages they would have burnt me;

nowadays they are content with burning my books."

In the 1930s: Freud's correspondence with Arnold Zweig in

Palestine

All his life, Freud was a productive and reliable letter

writer. He had an extensive correspondence with colleagues, with authors and

artists.

Freud also

continued his lively correspondence during this phase that was characterized

by the increasing threat of National Socialism. One of his preferred

correspondents was the Jewish author Arnold Zweig (1897-1968), whose

writings he used to read with interest. Zweig emigrated to Palestine in

1933. A close associate of Freud, Max Eitingon, had also sought

refuge there when he fled from Berlin. Numerous psychoanalysts and

psychoanalytic pedagogues followed him to Palestine and built up the

Palestine Psychoanalytic Society as early as 1934 (as of 1948: Israel

Psychoanalytic Society). The official language at that time was still –

German.

In Palestine, these emigrants held on to their European commitment and

engagement and were mainly interested in reforming the Jewish education and

health care system that was just being established. Some decades later, many

of them would play a prominent part in Israel and in the United States when

they were involved in psychoanalytic efforts aiming at helping Shoah victims

on the basis of well-founded psychoanalytical efforts to be able to deal

with their traumatic experiences more easily.

In Vienna and Berlin, many of them had been shaped by Siegfried Bernfeld,

a young psychoanalyst, pedagogue, socialist, and Zionist (1892-1953)

who had given the young psychoanalytic-pedagogic reform movement decisive

impetuses. His Viennese Baumgarten Nursing Home, founded in 1919

– a pedagogic pilot project where 240 Jewish war orphans were cared for

– was a microcosm of a modern Jewish education whose basic thoughts were now

taken up and realised in numerous Kibbuzim.

Arnold Zweig

was a friend of Eitingon in Palestine and described Eitingon's apartment

opposite that of Freud as "the most delightful ménage in Jerusalem"; and he

added: "and it is wonderful to have people so close who are so intimate with

you and who carry out your work so faithfully."

Like Bernfeld,

Zweig identified himself passionately with Zionism throughout his youth. In

1924, he joined the editorial staff of the newspaper Jüdische Rundschau,

and in 1925, he published his work "Das neue Kanaan" (the new Kanaan) in

which he expressed his identification with Zionism. In 1929, he published

the essay "Freud und der Mensch" (Freud and the human being) in the magazine

Die Psychoanalytische Bewegung.

The profound

correspondence between the two intellectuals began in March 1927; it ended

twelve years later with Freud's death. In spite of the geographical

distance, "Father Freud" – as Zweig often called him respectfully in his

letters – remained an amicable and affectionate advisor and companion of

Arnold Zweig during all those years.

In April

1932, Arnold Zweig took the risk of returning to Germany after a journey to

Palestine. On May 1, 1932, Zweig wrote to Freud: "What a mistake to

try to come back here! What remains intact at this moment of the Europe I

love and of Germany to which I in large part belong, the original source of

my strength and of my work? Why did I not stay over there in the heroic

scenery of Galilee or by the sea at Tel Aviv or at the Dead Sea."

And on May

29, 1932, Zweig added: "You touched on two difficult points which I have

thought about a great deal. My relationship to Germany and to my Germanness,

and my relationship to the Jews, to the Jewishness in me and in the world,

and to Palestine. This land of religions can, after all, be seen from other

points of view than just as a land of delusions and desires."

On August

18, 1932, Freud answered him. He had heard of the National Socialist

threats against Zweig and encouraged his friend to go on with their mutual

correspondence and their regular exchange of manuscripts: "So perhaps the

Nazis are playing into my hands for once. When you tell me about your

thoughts, I can relieve you of the illusion that one has to be a German.

Should we not leave this God-forsaken nation to themselves? I am going to

conclude now so that this letter may reach you more quickly and I send both

of you my sincere greetings."

In 1933, the

46 yearl-old Arnold Zweig did something that Freud, 31 years older, did not

seriously take into consideration: He emigrated to Palestine – or rather

stayed in the Promised Land after a journey to Palestine. Friends had

advised him to do so.

Zweig settled

in Haifa. Since he did not know any Hebrew, by and large at least, and since

he was additionally handicapped to learn the language because he was

partially sighted, the original euphoria quickly gave way to a sobering

disillusionment: He felt too little appreciated as a writer in Eretz Israel,

suffered under the depressing economic living conditions, was unable to

assimilate himself socially, and refused to identify himself completely with

Zionism. On January 21, 1934, only one month after his arrival in

Palestine, he wrote to Freud, obviously discouraged: "At one moment the

central heating did not function, at another the oil stove was smelling (…)

We are not prepared to give up our standard of living and this country is

not yet prepared to satisfy it (…) I don't care anymore about ‘the land of

my fathers'. I don't have any more Zionistic illusions either. I view the

necessity of living here among Jews without enthusiasm, without any false

hopes and even without the desire to scoff."

Seven days

later, on January 28, 1934, Freud replied: "I have long waited

eagerly for your letter (...) I am eager to read it, now that I know you are

cured of your unhappy love for your so-called Fatherland. Such a passion is

not for the likes of us."

And on

February 25, 1934, Freud added, referring to his own difficult situation

in Vienna: "You are quite right in your expectation that we intend to stick

it out here resignedly. For where should I go in my state of dependence and

physical helplessness? And everywhere abroad is so inhospitable. Only if

there really were a satrap of Hitler's ruling in Vienna I would no doubt

have to go, no matter where."

Two months

later, Zweig, in his need, sought help by way of a psychoanalytic treatment.

On April

23, 1934,

he wrote to Freud: "Dear Father Freud, I am taking up my analysis again. I

just cannot shake off the whole Hitler business. My affect has shifted to

someone who looked after our affairs for us in 1933 under difficulties. But

this affect of mine is an obsession. I don't live in the present, but am

absent.

During the

phase when he was threatened himself, Freud's greatest concern was the

survival of his family and of his analytic colleagues. Obviously, he saw

their emigration as a necessity – and yet had occasionally the deceptive

illusion that his psychoanalysis, his psychoanalytic magazines, and his

publishing house in Vienna would have a chance to survive. During this

phase, Freud was occupied with his "work produced in his later years": his

critical study in respect of religion and culture "Moses and Monotheism".

This book written by the almost 80 year-old cancer-stricken man was the

endeavour to understand the "never-ending anti-Semitism" and the murderous

hatred for "the Jews" within the framework of a historical dimension.

The more Freud himself was threatened by anti-Semitism, the more he

identified himself with his Jewish roots. The first two chapters of his

study of Moses were published in "Imago" in 1937, but only after Freud's

emigration to London was it completely published by a Dutch publishing

house.

In a letter

dated September 30, 1934 to Arnold Zweig, Freud outlined his thematic

and methodical approach: "The starting point of my work is familiar to you –

it was the same as that of your Bilanz.

Faced with the new persecutions, one asks oneself again how the Jews have

come to be what they are and why they have attracted this undying hatred. I

soon discovered the formula: Moses created the Jews. So I gave my work the

title: The Man Moses, a historical novel."

On

September 9, 1935, Freud thanked Zweig for having sent him his novel

Erziehung vor Verdun (instruction before Verdun). Freud was taken with

this work of his friend: "My daughter Anna is now reading Erziehung vor

Verdun and she keeps coming to me and telling me her impressions. We

then exchange views. You know that I imagine it was my warning which

restrained you from returning to Berlin, and I am still proud of this

achievement, and now it is more certain than ever that you should never go

near the German frontier again. You are too good for that. It is like a

long-hoped-for liberation. At last the truth, the grim ultimate truth, which

is nevertheless essential. You cannot understand the Germany of today if you

know nothing of Verdun and what it stands for."

Occasionally,

there are some hints appearing now and then in Freud's letters suggesting

that he was no longer able to push aside that his very own existence was

threatened by the National Socialists. On October 14, 1935, he wrote

to Zweig: "An anxious premonition tells us that we, oh the poor Austrian

Jews, will have to pay a part of the bill. It is sad (...) that we even

judge world events from the Jewish point of view, but how could we do it any

other way!"

In the

meantime, Arnold Zweig complained now more frequently about his life in

Palestine. On February 15, 1936, he wrote to Freud: "I struggle

against my whole existence here in Palestine. I feel I am in the wrong place

(...) What do you say? You and no one else restrained me from the folly of

returning to Eichkamp in May 1933, i.e. to the concentration camp and death.

Apart from you, of all my friends it was only Feuchtwanger who saw so

clearly. But what do you advise me to do?"

Freud was

moved by Zweig's misery. Only six days later, on February 21, 1936,

he replied: "Your letter moved me very much, It is not the first time that I

have heard of the difficulties the cultured man finds in adapting himself to

Palestine. History has never given the Jewish people cause to develop their

faculty for creating a state or society (…) You feel ill at ease, but I did

not know you found isolation so hard to bear. Firmly based in your

profession as artist as you are, you ought to be able to be alone for a

while. In Palestine at any rate you have personal safety and your human

rights. And where would you think of going? You would find America, I would

say from all my impressions, far more unbearable. Everywhere else you would

be a scarcely tolerated alien. In America you would also have to shed your

own language; not an article of clothing, but your own skin. I really think

that for the moment you should remain where you are. The prospect of having

access to Germany again in a few years really does exist (…) It is true even

that after the Nazis, Germany will not be what it was (…) But one will be

able to participate in the clearing-up process."

The

increasingly escalating deprivation of rights and persecution in Austria led

Freud to an increasingly more pessimistic – i.e. realistic – but also to a

fatalistic view of his possibility of existence in Vienna. On June 22,

1936, he wrote to Zweig: "Austria seems bent on becoming National

Socialist. Fate seems to be conspiring with that gang. With ever less regret

do I wait for the curtain to fall for me."

And towards

the end of the year 1937, his resignation seemed to have prevailed: "In your

interest I can scarcely regret that you have not chosen Vienna as your new

home. The Government here is different but the people in their worship of

anti-Semitism are entirely at one with their brothers in the Reich. The

noose round our neck is being tightened all the time even if we are not

actually throttled. Palestine is still British Empire at any rate; that is

not to be underestimated."

The emigration of the Viennese psychoanalysts and pedagogues

into exile

The expulsion of the intellectual elites from Vienna and

Austria in the 1930s was the most drastic turning point in the history of

science in Austria. Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic pedagogy – vigorously

enhanced by Freud – were completely destroyed in their own country of origin

and forced to emigrate – mostly to the United States.

As for the cultural and biographic damage suffered by the

psychoanalytic-pedagogic movement, its historic-biographical uprooting, it

was not able to recover from this setback for several decades.

Since the 1930s, the psychoanalytic movement as such can only be described

as an emigration movement. Most analysts succeeded in fleeing into

liberating exile; more than 20 of them, however, were murdered but up to the

1980s, hardly anybody was interested in their fate. The emigration of many

psychoanalysts had mainly been possible because they had various contacts

abroad, contrary to most other Jewish professional groups. The possibility

of emigrating to the United States depended, for example, mostly on the fact

that the emigrant had to find an American citizen who was prepared to make

an official statement that he was ready to financially support the emigrant

in case of emergency. In addition, there were many who were interested in

psychoanalysis and who had come to Vienna in the 1920s and 1930s – primarily

from the United States – in order to learn psychoanalysis at first hand at

its place of birth. Some of them had founded therapeutic schools and nursery

schools in Vienna, had translated Freud's writings, and had taught English

lessons for some analysts. Some of these American analysts – who were not

directly threatened in the 1930s due to their American citizenship – used

their position and contacts to help Viennese analysts to flee the country.

Some were even engaged illegally underground, procuring affidavits, false

passports, and money, and hiding analysts from the Nazis. The American

psychoanalyst Muriel Gardiner was said to be the boldest helper. In

particular, the courageous behaviour of the renowned psychoanalyst Richard

Sterba deserves to be mentioned who – although he was not personally

threatened as a Catholic – emigrated to the United States with his

colleagues out of solidarity.

Several

analysts – Edith Jacobson, Edith Buxbaum,

Rudolf Ekstein, Marie Langer,

Ernst Federn, Muriel Gardiner, and T. Erdheim-Genner are to be mentioned inter alia –

had intensively been engaged in the "illegal" resistance against the

National Socialists and had been detained for some time by the Gestapo.

Bruno Bettelheim

and Ernst Federn

survived the concentration camps of Dachau and

Buchenwald where they had been detained for one year and for seven years

respectively, and after their liberation and release from the camps they

became the founders of a psychology of terror.

Wilhelm

Reich, a combative antifascist who had published numerous pioneering studies

on the Psychology of Fascism in the 1920s and 1930s, suffered an especially

tragic fate. In 1933/34, he was excluded both from the International

Psychoanalytic Association as well as from the Communist Party, probably due

to his political engagement against the Nazis; his fate has been the object

of continued controversies up to this date.

Some figures

are to be mentioned: Out of the 149 members of the Viennese Psychoanalytic

Society – almost all of them were Jews – 146 emigrated up to the year 1939.

Almost all psychoanalytic pedagogues emigrated, most of them to the United

States. Despite the "Medicocentrism" (Paul Parin) prevailing in the United

States at that time, most of them succeeded in standing their ground in

their new homeland and in integrating parts of their professional identity

into the new culture of their homeland. Yet, the socially enlightening

atmosphere of departure that probably could only emerge in such a way as it

did in Vienna, had been extinguished. In the United States, there was hardly

any possibility of picking up the thread on a cultural level in this

respect. On the other hand, many of the young psychoanalytic pedagogues who

had been shaped by Sigmund Freud and Siegfried Bernfeld succeeded in doing

pioneering work in the psychoanalytic-pedagogic field. For example, Anny

Angel-Katan, Bruno Bettelheim, Siegfried Bernfeld, Peter Blos, Berta and

Stefanie Bornstein, Edith Buxbaum, Kurt Eissler, Rudolf Ekstein, Erik

Erikson, Ernst Federn, Anna Freud, Judith S. Kestenberg, Else Pappenheim,

Lili Peller, Emma Plank, Fritz Redl, Emmy Sylvester, Richard and Editha

Sterba are to be mentioned inter alia.

Freud's emigration – death in exile

As of 1936, the situation became more and more critical in

Vienna. The failed uprising of February 1934 had triggered a process of

disillusionment on the part of the left and led to another increase in the

emigration wave. Strong signs of fatalism were creeping in Freud's letters:

"Superfluous to say anything about the general situation of the world", he

wrote to his Hungarian colleague Ferenczi in April 1932.

The idea of emigrating himself, what friends fearing for his life had

advised him to do, appears now and then, but just to be rejected immediately

again. "Flight would be justified, I believe, only if there were a direct

danger to life", he wrote to Ferenczi in April 1933.

Freud wanted to hold out in Vienna as long as possible by any means. The

role of a refugee running away from the Nazis did not seem to be an

acceptable perspective of life for the almost 80 year-old cancer-stricken

man. After the failed uprising of February 1934 , he wrote to his son Ernst

Freud on February 20, 1934: "Either an Austrian fascism or the swastika. In

the latter case, we should have to go."

The birthday celebrations around May 6, 1936 on occasion of Freud's

eightieth birthday which received international attention, were a

possibility of providing a short diversion once again. Thomas Mann

personally read out his congratulation text at Freud's house in Berggasse

no. 19: "Freud and the future". He was elected a corresponding member of the

internationally renowned "Royal Society" in London; among international

press reports, in particular, the one written by the Swedish author Selma

Lagerlöf attracted attention.

|

Foto: © Archive S. Fischer Verlag

|

At the same

time, however, Freud was increasingly suffering from pain due to his

cancerous disease and had thoughts of dying. His letters, including those to

Arnold Zweig, were becoming more gloomy. His dependency on his most beloved

daughter Anna who had cared for him for years, was increasing more and more.

In letters she vividly described the panic among Viennese Jews by which she

did not, however, want to be infected. On March 11, 1938, following an

ultimatum delivered by Hitler, Freud recorded in his short memorandum "Finis

Austriae", on March 14, "Hitler in Vienna".

The Board of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society recommended its members who

were still in Vienna to emigrate. The synagogues were burning, Jews were

abused in the streets. On March 15, 1938, Freud's apartment and his

publishing house Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag were

searched; one week later Anna Freud was eventually arrested by the Gestapo

and summoned for interrogation – a shock for Freud. Events followed in quick

succession: Now he could no longer ignore the asylum offers made by several

governments, among others by that of Palestine. William Bullitt, American

Ambassador in France, Cordell Hull, American Secretary of State, the

American Consul General in Vienna, and Freud's longstanding friend Princess

Marie Bonaparte empathically used their contacts and intervened to get

permission for Freud to leave Vienna. On June 4, 1938, all the formalities

were completed: Freud emigrated with a part of his family via France to

London. The press spread the photograph showing Anna and Sigmund Freud in a

train compartment throughout the world. His last short letter dated June 4,

1938, still written in Vienna, was addressed to Arnold Zweig: "Leaving today

for 39, Elsworthy Road, London N. W. 3. Affect, greetings Freud." Zweig

answered him on June 18, 1938: "You are now in safety, no longer exposed to

years of vindictive persecution (...) your archives, your books, your

collections have been saved."

Freud's power

of observation and his art of formulating were unbroken. Immediately upon

his arrival in London, on June 6, 1938, he wrote a long, personal letter to

Eitingon in Jerusalem: "The emotional situation is hard to grasp, barely

describable. (...) We have become popular all of a sudden."

And an almost

reconciliatory tone became noticeable when he noted shortly after his

arrival in London: "for one had still very much loved the prison from which

one has been released."

In London,

too, the 82 year-old Freud went on with his scientific writing. He completed

his "Moses", and in July 1938, he began with his dense work "An

Outline of Psychoanalysis".

Freud was

now increasingly overwhelmed by his cancerous disease from which he had been

suffering since the year 1923. In September 1938, he underwent a last

surgery, from which he would not recover. One year later, in September 1939,

he could no longer stand the pain. On September 21 and 22, his physician

administered to him several doses of morphine, and in the early morning

hours of September 23, 1939, the wise old man died during his exile

in London.

Of the horror

that was to follow, Freud did not see anything. Four of his sisters were

murdered in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz.

[Deutsch]

The Authors:

Roland

Kaufhold, born

1961, Dr. phil, Dipl.

Päd., is a teacher for handicapted children and a writer and publisher in

Cologne, Germany. Author of the

books: (Ed.): Annäherung an Bruno Bettelheim, Mainz 1994; (Ed.): Ernst

Federn: Versuche zur Psychologie des Terrors, Gießen 1999 (Psychosozial

Verlag); Kaufhold/Lieberz-Groß (Ed.): Deutsch-israelische Begegnungen,

psychosozial Heft 83 (1/2001); Bettelheim, Ekstein, Federn: Impulse

für die psychoanalytisch-pädagogische Bewegung, Gießen 2001 (Psychosozial

Verlag).

Coauthor in: David James Fisher (2003): Psychoanalytische

Kulturkritik und die Seele des Menschen. Essays über Bruno Bettelheim,

Gießen; (Ed.) (2003): "So können sie nicht leben" - Bruno Bettelheim (1903 -

1990), Zeitschrift für Politische Psychologie Nr. 1-3/2003.

One of his studies is published in english on the

Website

dedicated to Edith Buxbaum (1902-1982), the editor is Esther Helfgott,

Seattle. The translator is Prof. Hamida Bosmajian

(Seattle).

Internet:

http://www.suesske.de/index_kaufhold.htm

Hans-Jürgen Wirth,

Prof. Dr., is a psychoanalyst and analytic family therapist, practicing in

own office. Member of the German Psychoanalytical Association (DPV) and the

International Psychanalytic Association (IPA). Professor of „Psychoanalysis

with Special Emphasis of Prevention, Psychotherapy and Psychoanalytic

Socialpsychology“ at the Department of Human and Health Sciences at the

University of Bremen. University lecturer of psychoanalysis, depth

psychologically founded psychotherapy and psychoanalytically oriented family

and social therapy at the "Institut for Psychoanalyis und Psychotherapy

Giessen e. V.", an Institute of the German Psychoanalytical Association (DPV).

Owner and leader of the Publishing company

Psychosozial-Verlag. Editor of the German book series "Bibliothek der

Psychoanalyse" (Psychosozial-Verlag), editor in chief of the journal "psychosozial",

author of numerous articles and various books on the applications of

psychoanalysis. English books: "9/11 as a Collective Trauma and other Essays

on Psychoanalysis ans Society" and "Narcissism

and Power. Psychoanalysis of Mental

Disorders in Politics".

Critics have called the

book Narcissism and Power (2002), written by Hans-Jürgen Wirth a 'masterpiece

of political psychology'. In 9/11 as a Collective Trauma he presents a

collection of his interesting essays about the psyche and politics. He

reflects on the psychic structure of suicidebombers, and analyzes the

psycho-political causes and the cosequencesof the Iraq war.

The other

essays focus on xenophobia and violence, the story of Jewish psychoanalysts

who emigrated to the United States from Nazi-Germany and the human image of

psychoanalysis.

Internet:

www.hjwirth.de

Notes:

Peter Gay (1988): Freud. A Life for Our Time. New York/London (W. W. Norton

& Company), p. 599.

ibid., p. 592-593.

Sigmund Freud (1961): Civilization and Its Discontents. With a biographical

introduction by Peter Gay. New York/London, p. 111-112.

Ernst Federn (1988): Die Emigration von Sigmund und Anna Freud. Eine

Fallstudie. In: F. Stadler (Hg.): Vertriebene Vernunft II. Emigration und

Exil österreichischer Wissenschaft 1930-1940.

Munich, Vienna

1988, p. 248.

See also Bernd Nitzschke (1996): Wir und der Tod. Essays über Sigmund Freuds

Leben und Werk. Göttingen (Sammlung Vandenhoeck); Peter Schneider (1999):

Sigmund Freud. Munich (dtv).

Gay (1988), p. 19.

ibid., p. 12.

Ernest Jones (1984): Sigmund Freud. Leben und Werk, Munich (dtv), Vol. 2, p.

139.

Gay (1988), p. 6

ibid., p. 603

ibid., p. 140

Freud (1926), in: Nitzschke (1996), p. 118; see also Gay (1988), p. 597

Gay (1988), p. 204

ibid.

Gay (1988), p. 205. For more details see: Susann Heenen-Wolff (1987): "Wenn

ich Oberhuber hieße ..." Die Freudsche Psychoanalyse zwischen Assimilation

und Antisemitismus. Frankfurt am Main (Nexus).

Gay (1988), p. 205

Ludger M. Hermanns (1982): John F. Rittmeister und C. G. Jung. In: H.-M.

Lohmann (ed.) (1985): Psychoanalyse und Nationalsozialismus. Beiträge zur

Bearbeitung eines unbewältigten Traumas. Frankfurt/M. (Fischer TB), 137-145.

See also the impressive statements of Thomas Mann (1935) and

Ernst Bloch regarding Jung which are contained therein; the latter described

Jung literally as a "psychoanalytic fascist".

Gay, (1988), p. 448

ibid, p. 597

Nitzschke (1996), p. 50

Gay, (1988), p. 592-593

Ruth Kloocke (2002): Mosche Wulff. Zur Geschichte der Psychoanalyse in

Rußland und Israel, Tübingen (edition diskord).

Without claiming completeness we would like to mention: Maria and Martin

Bergmann, Bruno Bettelheim, Yael Danieli, Nathan Durst, Ernst Federn, M.

Jucovy, Hans Keilson, Judith S. Kestenberg, Hillel Klein, R. Moses, Yehuda

Nir, Martin Wangh, and Zvi Lothane.

As literature we would like

to mention: M. S. Bergman; Jucovy, M. E.; Kestenberg, J. S. (ed.)

(1982): Kinder der

Opfer, Kinder der Täter. Psychoanalyse und Holocaust. Frankfurt M.

(Fischer). To Hans Keilson we would like to mention: Roland Kaufhold (2008):

"Das Leben geht weiter". Hans Keilson, ein jüdischer Psychoanalytiker,

Schriftsteller, Pädagoge und Musiker, in: Zeitschrift für psychoanalytische

Theorie und Praxis (ZPTP), Heft 1/2-2008, S. 142-167.

Roland Kaufhold (2008): Siegfried Bernfeld - Psychoanalytiker, Zionist,

Pädagoge. Vor 55 Jahren starb Siegfried Bernfeld, in: TRIBÜNE, Nr. 185 (H.

1/2008), p.178-188.

See previous footnote and: Manuel Wiznitzer: Arnold Zweig: Das Leben eines

deutsch-jüdischen Schriftstellers, Frankfurt/M.; Wilhelm von Sternburg

(1998): Um Deutschland geht es uns. Arnold Zweig. Die Biographie, Berlin

(Aufbau).

Freud, Ernst (ed.)

(1970): The

Letters of Sigmund Freud and Arnold Zweig. London (The Hogarth Press), p.

37.

E. Freud (1970), p. 43

ibid., p. 45

ibid., p. 55-57

ibid., p. 59

ibid., p. 65-66

ibid., p. 73

Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol.

23, p. 1-137.

See also: Bernd Nitzschke (1996): "Freud, der Mann Moses und der

Antisemitismus" and "Judenhaß als Modernitätshaß. Über Freuds Studie 'Der

Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion' (1937/39)", both in: Nitzschke

(1996), p. 40-53, p. 149-183.

Zweig 1934

E. Freud (1970), p. 91

ibid., p. 110

Gay (1988), p. 610

E. Freud (1970), p. 120-121

E. Freud (1970), p. 122

ibid., p. 133-134

ibid., p. 154

See Roland Kaufhold (2001): Bettelheim, Ekstein, Federn: Impulse für die

psychoanalytisch-pädagogische Bewegung. Gießen (Psychosozial-Verlag)

www.suesske.de/kaufhold-1.htm

;

the

same author (2003): Spurensuche zur Geschichte der die USA emigrierten

Wiener Psychoanalytischen Pädagogen, in: Luzifer-Amor: Geschichte der Wiener

Psychoanalytischen Vereinigung (ed. Thomas Aichhorn), 16:31 (1/2003), p.

37-69; Hans-Jürgen Wirth (2002):

Narcissism and Power. Psychoanalysis of Mental Disorders

in Politics, Gießen (Psychosozial-Verlag); the same author (2005):

9/11 as a Collective Trauma and other Essays on

Psychoanalysis ans Society, Gießen (Psychosozial-Verlag); Hans-Jürgen Wirth/Trin

Haland-Wirth (2003): Emigration, Biographie und Psychoanalyse.

Emigrierte PsychoanalytikerInnen in Amerika. In: Kaufhold

et. al. (ed.) (2003), "So können sie nicht leben" - Bruno Bettelheim

(1903-1990), Zeitschrift für politische Psychologie 1-3/2003, p. 91-120,

David James Fisher (2003): Psychoanalytische Kulturkritik und die Seele des

Menschen. Essays über Bruno Bettelheim unter Mitarbeit

von Roland Kaufhold et. al. Gießen (Psychosozial-Verlag).

www.suesske.de/buch_fisher.htm;

the same author:

(2008): Bettelheim: Living and Dying: Contemporary

Psychoanalytic Studies Series (Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi)

cf. Kaufhold (2001)

www.suesske.de/kaufhold-1.htm

cf. the website

www.Edithbuxbaum.com

cf. also Kaufhold (2001)

Roland Kaufhold (ed.) (1999): Ernst Federn - Versuche zur Psychologie des

Terrors. Gießen (Psychosozial-Verlag).

http://www.suesske.de/kaufhold-2.htm

Karl Fallend; Bernd Nitzschke (ed.) (2002): Der "Fall" Wilhelm Reich.

Beiträge zum Verhältnis von Psychoanalyse und Politik, Gießen

(Psychosozial-Verlag).

http://www.psychosozial-verlag.de/psychosozial/details.php?p_id=147&ojid=e881d763bc0830fff0ec030d

Gay (1988), p. 588

ibid., p. 593

ibid., p. 594-595

ibid., p. 618

E. Freud (1970), p. 160-161

Gay (1988), p. 630-631

Gay (1988), p. 629

|