|

Cultural Heritage:

The Wooden Synagogues of Lithuania

by Joyce Ellen Weinstein

[Deutsch]

The only thing one can say with certainty about the

wooden synagogues of Lithuania is that they are rotting away. Some years ago

efforts were made to raise money for their restoration, but nothing came of

it, for the most part because the remaining Jewish community is much too

small to mobilize efforts. Money is in short supply, and no one is certain

whether the buildings belong to the municipality, township or region in

which they are located.

According to Rosa Bielioiskiene, Chief Curator of the

Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, the newest of the synagogues is close to one

hundred years old. The oldest of these Baroque buildings, dating from the

seventeenth century, were in Valkininkai, Jubarkas, Saukenai and

Vilkaviskis, villages that are scattered throughout the country. These

villages had sizable Jewish populations; in some cases they were completely

Jewish. Construction of wooden synagogues continued until the early part of

the twentieth century, with more than twenty-three constructed between the

nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. After WWII, only stone

structures were constructed. After WWI almost nine percent of the total

population of Lithuania was ethnic Jewish and up until the Second World War

there were 500 to 600 different kinds of Jewish prayer houses in the

country. Today there are ten synagogues or community centers in use.

Records show that Jews were already settled in Lithuania

well before the fourteenth century. In the mid-sixteenth century Lithuania

and Poland merged under common government and legislation. During the late

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the complex political relationship of

Poland, Lithuania and Russia, a subject well outside the pervue of this

article, brought many more Jews to Lithuania, mostly from Poland. One of the

first buildings constructed in each new Shtetle was the synagogue. Because

of the proliferation of forestland in Poland, the settlers were experienced

in using wood. Lithuania's vast woodland, similar to Poland's in its

magnitude, made construction of the synagogues cheap and easy. There is no

definitive evidence as to whether Jews or Lithuanians actually built the

structures. It is generally assumed that Jews at least ordered the

construction to their specifications. They were able to tell the workers how

to build what they wanted. Later, into the twentieth century, professionals

and architects were hired.

The interiors of some of the synagogues were elaborately

decorated. It is probable that except for very early on, Jews painted the

interiors. They might have seen the elaborate ornamentation inside a church.

Inspired by that model, the artists taught themselves how it was done. One

must bear in mind, however, that there was no special tradition or imagery

for the Jewish artist to draw upon, and he had to invent the imagery as he

went along. The artist would work on the decoration after finishing his

day's work. It is possible that someone a little more prosperous in the

village requested and paid for the work, but most probably it was purely a

labor of love. (This is only an educated assumption with no definitive

corroborating information.) Experts now characterize the decoration in the

synagogues as "folk art."

The synagogue in Pakruojis

Today, there are only eight wooden synagogues still

standing in remote villages: Pakruojis, Tirksliai, Seda, Zeizmariai,

Kurkliai, Alanta, Rozalimas and Kaltinenai. With my guide and interpreter,

Lilia Jureviciene, provided by Europos Parkas Open Air Museum of the Center

of Europe, I was able to visit five of the eight synagogues. It was an

affecting adventure. Upon arriving at a village, Lilia would ask a local

where the wooden synagogue is located. Typically, the first response would

be, "I don't know-- there is no wooden synagogue here." Eventually, someone

would recall the location of the building.

In Kurkliai, a village of 117 families, located about 100

kilometers northwest of Vilnius, we found the synagogue behind several very

old wooden cottages. Built somewhere between 1915 and 1939, it is similar in

style to eighteenth-century Romanticist/Historicist architecture. The almost

square building is one story, although the little corner tower with a small

peaked roof accommodated stairs that led up to the women's balcony. The

façade is plain with some elements of Moorish styling in the windows; that

is, they are narrow and high with a peaked triangle as a crown. It is not

known what the glass in the windows actually looked like. Today the windows

are boarded up.

The synagogue in Kurkliai

Generally, wooden synagogues took on the appearance of

barns so as not be conspicuous. To avoid competing with the churches that

were located in the center of town, synagogues were usually erected in areas

reserved for the Jewish quarter. But there are conflicting stories about

where Jews lived. According to some people we interviewed, Jews were

scattered throughout the village and lived near their shops, wherever they

were located. Others claimed Jews lived in specific areas. In either case,

for safety, buildings were enclosed and monumental. In earlier times there

were no significant details on the façade to identify them. However in

Kurkliai, because the synagogue is of a more recent date, a Star of David

can be seen on the facade of the building. In Kurkliai the foundation is

made of bricks, although other foundations were made of stone. Each

construction is characteristic of building foundations.

Since the interiors of most of the synagogues have been

destroyed, we can only infer the layout. Based on measurements of the

building in Kurkliai, technical plans were drawn by a Mr. P. Jurenas in

1935. He concluded that the synagogue was divided into two rooms, one

slightly larger than the other. The plans indicate the staircase to the

women's balcony. In Kurkliai, as in other villages, during the Soviet

occupation the synagogue was used as a warehouse and storage building for

cars, horses, pigs and other animals. What makes the Kurkliai synagogue

remarkable is that the inside has been cleaned. Angele Dudiene, a secondary

school teacher of the natural sciences, has become the village specialist in

Jewish history. She teaches the subject in her classes. It is unclear

whether her instruction is state mandated, or she has decided to make it her

personal mission. A compassionate person with considerable initiative, she

took it upon herself to mobilize some of the townspeople and students to do

the work of clean-up. She has made the villagers aware of the building as a

religious institution. "This," she says, "is reason enough to restore it."

During the cleaning she found old newspapers and documents, including some

unspecified objects that she gave to the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in

Vilnius. She has offered to have some of her teaching materials translated

from Lithuanian to English and to forward them to me when school reopens.

They are locked in her classroom for the summer.

The synagogue in Zeizmariai

It is usual that one person in the village holds the key

to the synagogue, possibly the mayor. In Zeismarai, however, it is held by

an eighty-two year old Russian woman who lives near the synagogue. She was

once the caretaker of animals that were stored in the shul by the local

veterinarian during the Soviet occupation. She says, "I hold the key because

I am such a good person. Ask anyone in the village what a good person I am.

They will all tell you this is true." The synagogue in Zeismarai is quite

large, with three or four rooms on the lower floor. Although we were able to

go inside it is impossible to tell exactly how many rooms there were. The

walls and beams are collapsing, torn down or lying on the ground. Trash is

everywhere. There is a second floor but it is completely inaccessible.

Because of the size of the structure it is assumed that the Jews in the

village were prosperous.

On

one of the doors one can still see a silhouette of the mezuzah (right).

According to our Russian friend, the Jews here were not ghettoized but lived

all over the town and owned a number of shops. Now, she says, "The synagogue

seems to stand more for a monument to the killing of Jews instead of a

religious institution." Last year some people from Israel, Moscow and the

USA visited Zeismarai and organized a candle-lit concert on the grounds. The

American supposedly left some money for caretaking. On

one of the doors one can still see a silhouette of the mezuzah (right).

According to our Russian friend, the Jews here were not ghettoized but lived

all over the town and owned a number of shops. Now, she says, "The synagogue

seems to stand more for a monument to the killing of Jews instead of a

religious institution." Last year some people from Israel, Moscow and the

USA visited Zeismarai and organized a candle-lit concert on the grounds. The

American supposedly left some money for caretaking.

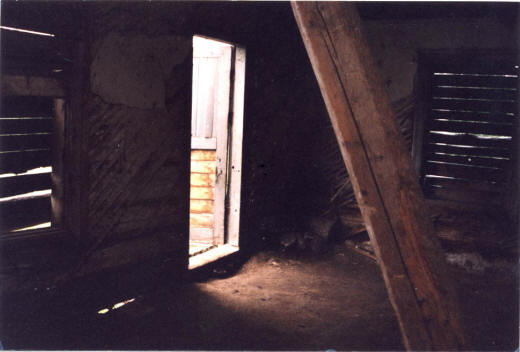

Interior of the synagogue in

Zeizmariai

Our visits to the five villages created a variety of

responses. Some people were reluctant to talk with us at first, then,

wouldn't stop, as if they needed to unburden themselves. Others literally

ran away, when we told them what we wanted. Still others just stood nearby

and listened. In Pakruojis two drunken men sitting on their porch yelled

very loudly at us in a threatening way. One woman made it very clear that

Jews never occupied the house she was living in, even though it was right

next to the synagogue and clearly in the Jewish quarter. In Rozalimas, a

woman thought it funny that she is now living in the house once occupied by

the Rabbi and laughed as she spoke about it. Nevertheless, and perhaps

surprisingly, most people we spoke to praised their Jewish neighbors. They

said "We all loved the Jews. They always helped people by giving them things

and money. We can't understand why such terrible things happened."

Because of the curious attitudes of those we encountered

and the uncertainty surrounding the question of the synagogues, I resolved

to learn the government's official position on the subject. I gained easy

access to Ms. Diana Varnaite, Director of the Department of Cultural

Heritage of Lithuania, and Mr. Alfredas Jomantas, Head of International

Cooperation, Department of Cultural Heritage Protection. According to these

high officials, the government of Lithuania is taking serious steps to raise

awareness of the rich cultural heritage left by the Jews and their important

role in Lithuania's cultural history. For the European Heritage Days, a

major event planned for September, Lithuania was appointed to choose

the team for Jewish Cultural Heritage Awareness. Seminars, lectures and

other events have been planned to educate and raise consciousness. According

to Ms Varnaite, the launching of cultural tourism, protection of monuments

and education are top priorities. She says, "It important to begin now while

the material heritage is still in the memories of the people."

But a dilemma remains. If the synagogues are restored,

what will they be restored to? What will they become? Some suggestions

include multicultural centers, museums or art schools. One village had

considered turning its old synagogue into a disco, but was short on funds.

All images © Joyce

Ellen Weinstein

[Deutsch]

Joyce Ellen Weinstein

Born

in New York, Joyce Ellen Weinstein later moved to Washington, DC. USA, She

received her Masters in Fine Arts from the City College of New York, and

attended The Art Students League. She received fellowships to Mishkenot

Sha’ananim,

Jerusalem, Israel; Blue Mountain Art Center, New York, as

resident painted a mural in Prague, Czech Republic. In 2000/2004/2005 she

was Artist in Residence at Europos Parkas, Open-Air Museum of the Center of

Europe, Vilnius, Lithuania. Her works are in permanent collections of the

National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC; Hebrew Union College

Institute of Religion Museum, NYC., Gallerie-Junge KunstWerkStart, Vienna,

Austria; The Social-Cultural Center, Prague, Czech Republic; Amnesty

International; Einchen Americe, Princeton, New Jersey, among others. Works

are in private collections in the US and Europe. She is included in “Fixing

the World: Jewish American Artists of the Twentieth Century”, by Ori Z

Soltes, New England University Press. Ms. Weinstein will be exhibiting at

the Biennale Internazionale Dell’Arte Contemporanea in Florence, Italy

December 2005.

Works of Joyce Ellen

Weinstein based on the wooden synagogues

Joyce Ellen

Weinstein's website

hagalil.com 07-06-2005 |